—

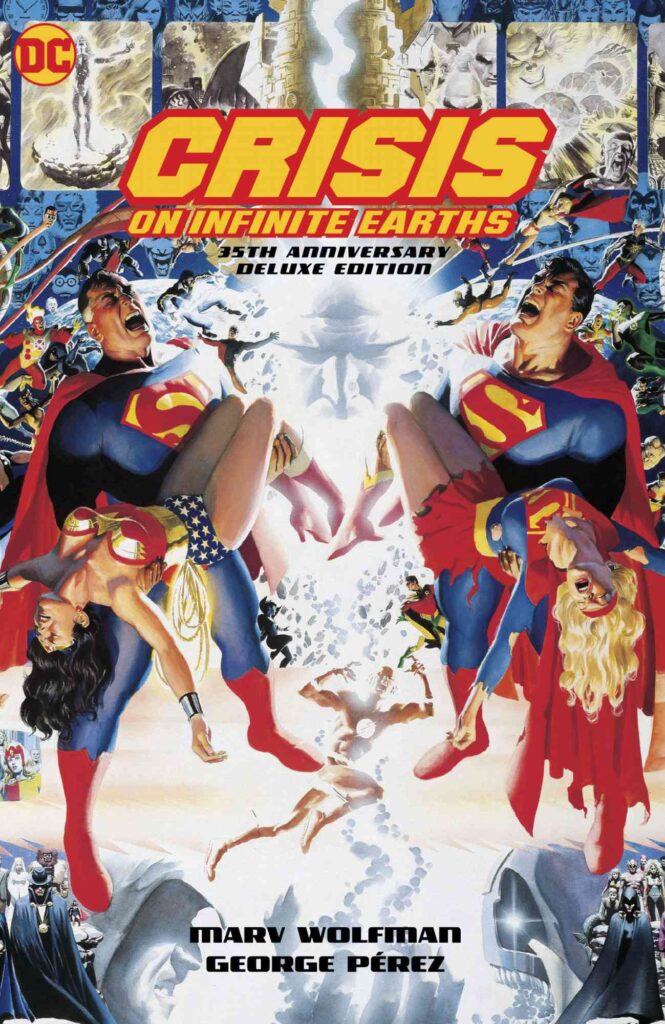

Modern Age Earth-0—as pictured in Crisis on Infinite Earths #11 by Marv Wolfman & George Pérez (1986)

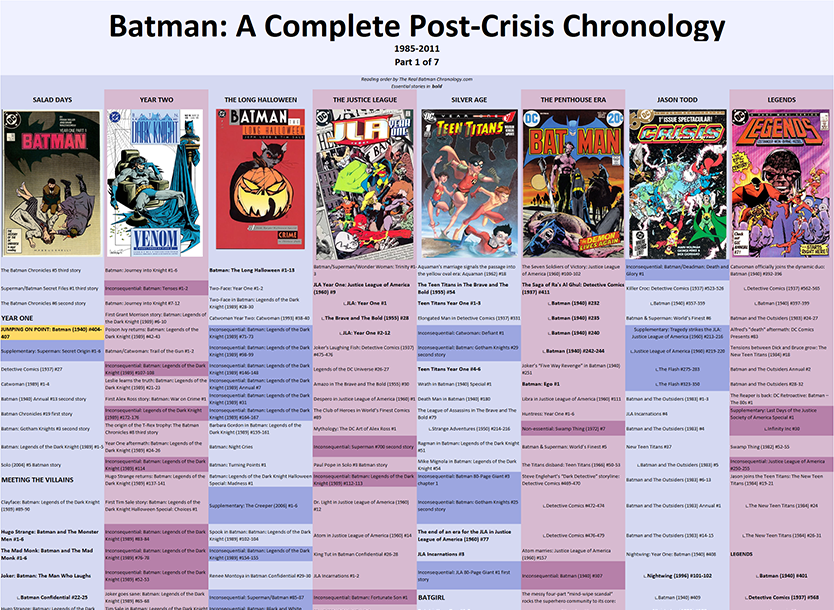

With special thanks to Chris J Miller’s Unauthorized Chronology of the DCU, Mike Voiles’ Amazing World of Comics, Michael Kooiman’s Cosmic Teams, Tenzel Kim’s Unofficial DCU Guide, Read Comic(s) Online, Ivan, Valheru, Ashley Jean Mastrine, Ross Holtry, Renaud Battail, Elias M Freire, Frank Fernandez, Martín Lel, and Troy Doliner, the Batman Chronology Project proudly presents the Modern Age Batman chronology, highlighting the history of the Batman of the pre-Flashpoint EARTH-0. This chronology could also be labeled the post-Crisis Earth-0—although, depending on your point of view, Crisis could refer to Crisis on Infinite Earths, Infinite Crisis, or Final Crisis. The Earth featured on this timeline was first known simply as the unlabeled primary EARTH (following Crisis on Infinite Earths), then retroactively called PRE-ZERO HOUR EARTH-0 (following Zero Hour), then called NEW EARTH (following Infinite Crisis and 52), then called EARTH-0 (following Final Crisis), then retroactively called PRE-FLASHPOINT EARTH-0 (following Flashpoint). The Modern Age history comprises Batman and Batman-related DC publications ranging primarily from 1985 through 2011.[1]

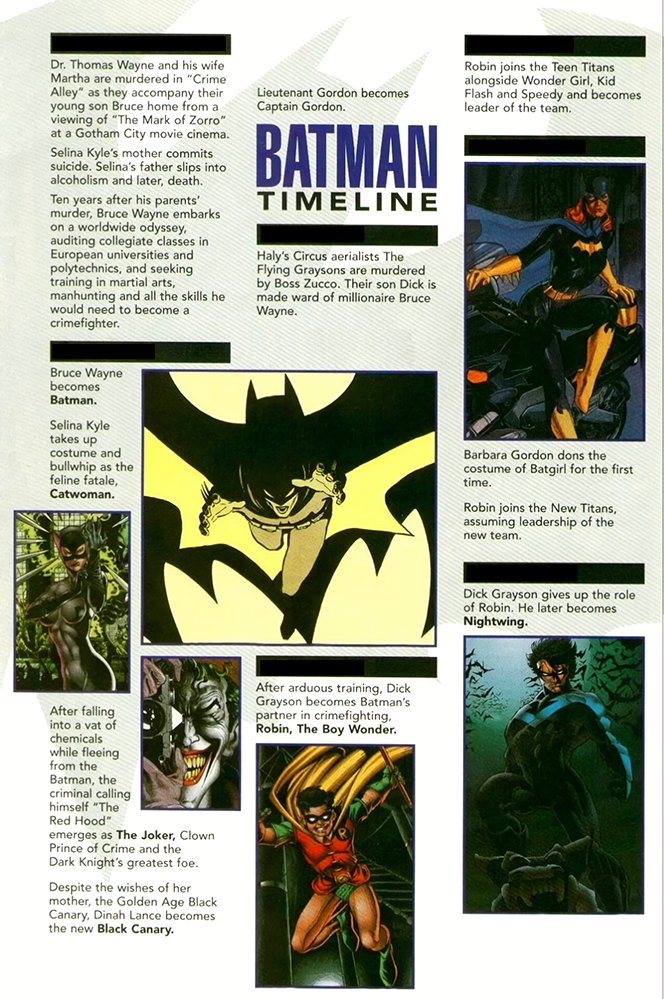

Diegetically, the Silver/Bronze Age ends with the Crisis on Infinite Earths (1985-1986), which spawns the Modern Age timeline, which itself is comprised of mashed-up altered versions of previous continuities. Golden Age material is reimagined as spanning from the 1940s up until Bruce’s birth, while some of Batman’s Golden Age and Silver/Bronze Age narrative gets reimagined as happening in his first ten years, which I’ve categorized as Batman’s “Early Period.” Batman’s “Early Period” begins with Miller’s “Year One” and Denny O’Neil’s “Shaman” (Legends of the Dark Knight #1-5).[2]

_______________________________

When building a Modern Age timeline, we must understand Batman’s publishing history. By the late 1950s/early 1960s, DC editors feared that their entire line, with a now twenty year-plus history dating back to the 30s and 40s, might be in need of a reboot. Leaning on the concept of the multiverse, the primary line superheroes were retconned as wholly separate characters from versions that had their origins in the 30s and 40s. Heroes that had gone on adventures in World War II, for example, became the older Golden Age heroes of Earth-2, while the younger primary line heroes (active in the 50s and 60s) became the main heroes of the Silver Age Earth-1. For Silver Age Earth-1 Batman, his reboot began around 1959-1960.[3] The rise of the multiverse saw a terracentric taxology, featuring not only the aforementioned Earth-1 (the home of Silver Age Batman) and Earth-2 (the home of the original Golden Age Batman), but also Earth-4 (the home of the Charlton heroes), Earth-S (the home of the Fawcett heroes), Earth-X (the home of the Quality heroes), ad infinitum.

By the mid 1980s, DC was ready to reboot again. Crisis on Infinite Earths was published in 1985-1986, not only resetting Batman as a character, but also functioning as an earth-altering, time-shattering crossover event that folded several character universes into one universe with one collective history, mashing together all the previous eras’ Earths (1, 2, 3, S, X, etc) to create a single “New Earth” (aka Earth-0). Crisis also erased Batman’s storied forty-six-year history, replacing it with a relative blank slate (aside from a group of wired-in Golden, Silver, and Bronze tales made canon via reference or flashback). In fact, because there was a void where Batman’s history used to be, writers continued to fill gaps even as late as 2011. Contrary to popular belief, DC’s publication of Crisis was not a reaction to a plague of continuity errors across its line. While it’s true that it was partly commissioned out of the notion that DC’s continuity was overly complex (and therefore off-putting to mainstream readership), there really weren’t too many continuity snarls to speak of in the early to mid 1980s, especially if compared to the canon problems yet to come. Besides this conception (or misconception, depending on your perspective) of DC’s excursive continuum requiring revision as a band-aid, we can say with undeniable certainty that the Crisis was green-lit for the following reasons. First, it was a compelling story idea. Second, it had potential to be financially-lucrative. (DC needed a shot in the arm since Marvel was beating them in sales.) And third, it allowed for DC to combine all of its superhero properties, many of which were recently purchased, into one solidified universe. Narratively, the story of Crisis goes as follows: The super-being known as the Anti-Monitor (along with the Spectre) combines a myriad of universes into a single universe with one collective history. Bear in mind, while the Anti-Monitor merges hundreds of thousands of Earths into DCU’s new main Earth, an unspecified number of alternate universes and multiverses (i.e. the Marvel Multiverse, the Image Multiverse, Wildstorm Universe, various Elseworlds universes, and more) remain unscathed and out of his vast reach. In this way, the omniverse (aka multi-multiverse) continues to exist in spite of Crisis‘ insistence that it merges everything.[4][5]

Of course, the Crisis didn’t simplify things—it actually had the opposite effect, greatly complicating things. In the wake of the Crisis, from 1986-1987, continuity wasn’t really set in stone. Scholar Mike Voiles goes so far as to fully separate this immediate post-Crisis continuity from the rest of the Modern Age, referring to it as the “Merged Earth” timeline. Site contributor Frank Fernandez acknowledges this viewpoint, citing that continuity wasn’t really concretized until John Byrne’s Man of Steel, Byrne’s Superman Vol. 2 #1, and Pérez’s Wonder Woman Vol. 2 #1 (1986-1987), certain Secret Origins Vol. 2 stories in 1987, or even as late as Hawkworld #1 in 1989.

In 1994, another big editorial shake-up took place in the form of Zero Hour: Crisis in Time. In its narrative, Green Lantern Hal Jordan becomes symbiotically-linked to the cosmically-powered being known as Parallax. Jordan alters time, compacting the entire DCU timeline into fewer “in-story years.” Those “in-story years” then became restructured so that they led up to 1994 (the year of the tale’s publication), but then later restructured so that they led up to 1998, then 1999, then 2000, and then 2002. Another way of explanation is to say that a sliding timescale (or floating timeline) was created that used Zero Hour as a place-marker. (This literary phenomenon—unique to serialized media—is also aptly known as sliding-time.) DC editors could now quietly slide the debuts of the major heroes to a more current date, thus continuously keeping stories contemporary without the utilization of a catastrophic reboot that would interrupt and restart everything. Following a slide to 1998 (as made clear via visual “x years ago” timelines released in Batman Villains Secret Files and Origins #1 and Green Lantern Secret Files and Origins #1) and a slide to 1999 (as made clear via a visual “x years ago” timelines released in JSA Secret Files and Origins #1 and DCU Heroes Secret Files and Origins #1), the year 2000 was technically the last time DC officially slid their timeline (as made clear via a visual “x years ago” timeline released in Guide to the DC Universe 2000 Secret Files and Origins #1), but it’s apparent that the Zero Hour place-marker was shifted once more to 2002 based upon overall writer consensus regarding character ages and specific references in the late 2000s.[6][7] DC editors stopped shifting the timeline after the the unofficial move in 2002, but would have likely continued the trend if not for a reboot in 2011 (but we’ll get to that later).

Because of the time-alterations associated with Zero Hour, some parts of Batman’s past obviously changed yet again in 1994. It’s important to understand that some DC editors wanted Zero Hour to function the exact same way as the original Crisis, meaning they wanted a full reboot i.e. a blank historical slate leading up to 1994. 2015’s Convergence arc confirms this fact by officially referring to the chronology that spans Crisis #11 through Zero Hour as the “pre-Zero Hour timeline.” (Some folks that share this view use the term “Sigma timeline” instead.) While my Modern Age Batman chronology gives a blank slate for everything prior to Crisis #11-12, I’m hesitant to do the same for Zero Hour. Zero Hour has been time-slid (from 1994 to 1998, to 1999, to 2000, and then to 2002), meaning that—if it were a true reboot—only stories published from 2002 to 2011 would be officially Modern Age canon, rendering everything prior to that as mere retroactive reference material. To this day, DC promotes (albeit vaguely) the idea of two separate continuities within the Modern Age: a pre-Zero Hour timeline (aka Sigma timeline) and a post-Zero Hour timeline (aka pre-Flashpoint timeline aka Modern Age Proper). I don’t buy that. Yes, Zero Hour introduced sliding-time to the DCU, but it changed very little narratively. Almost every single retcon that Zero Hour caused—from Batman’s urban myth status to Joe Chill’s erasure to the further muddling of Hawkman’s origin—was quickly ignored and reversed anyway, thus rendering Zero Hour as the very definition of a soft reboot (and barely one at that). To reiterate: in my view, Zero Hour was never a real reboot—and, even if we were to label it as such, it would definitely fall into the soft reboot category anyway. Notably, 2004’s Superman: Birthright revised Superman’s origins, but it is considered by most to be a soft reboot, having little effect on any other character other than the Man of Steel.

In 2006, Infinite Crisis was published, shaking the roots of the DCU to its foundations once again. The story’s narrative reveals that Superman from the original Earth-2, Superboy from the old Earth-Prime, and Alexander Luthor Jr from the old Earth-3 (all characters whose Earths were erased from existence during the original Crisis) have been watching the DC Universe from within a limbo pocket universe to which they have been exiled. Years have passed and they aren’t too happy with what they’ve seen. This unhappiness leads them to break out of their prison, which unleashes intense vibrational ripples that distort the fabric of time. Once again, time was adjusted significantly and Earth-0 was recreated again. In fact, for Batman specifically, much of the character-metamorphosis that happened during Zero Hour was reversed or undone, as mentioned above. Also, 52 brand new parallel Earths were not only added to the mix but, thanks to Infinite Crisis, were also retconned to have always existed. Our chronology reflects all of the changes made by Infinite Crisis. (Oddly enough, while DC considers the non-reboot/soft reboot of Zero Hour to be a full reboot, it doesn’t seem to offer the same courtesy to Infinite Crisis, despite the fact that Infinite Crisis actually functioned way more like a legit reboot than Zero Hour ever did! Go figure. From DC’s perspective, the reason for this outlook is likely because Zero Hour contemporized DC events while Infinite Crisis didn’t. However, the logic here is terribly flawed because Zero Hour didn’t change any story whereas Infinite Crisis changed the whole story. Clearly DC’s emphasis on the term “reboot” has to do with contemporization over alteration of story. I would place emphasis on the reverse and I certainly have on this website.)

Just as there is debate over whether or not the Modern Age should be split between pre and post-Zero Hour timelines, there is a similar (albeit smaller) debate whether or not the Modern Age could be split at Infinite Crisis. Frank Fernandez believes there is some merit to this theory, which includes a Modern Age consisting of pre-Infinite Crisis (1987-2006) and a post-Infinite Crisis (2006-2011) timelines. And depending on one’s view of the combination of Zero Hour, Infinite Crisis, and Superman: Birthright in terms of their reboot statuses, Fernandez posits another possibility that could include up to five distinct Modern Age continuities—Voiles’ “Merged Earth” timeline (1986-1987), a pre-Zero Hour timeline (1987-1994), a post-Zero Hour timeline (1994-2004), a post-Superman: Birthright timeline (2004-2006), and a post-Infinite Crisis timeline (2006-2011). Let’s not forget that Superman: Birthright itself was slightly revised by Superman: Secret Origin in 2010. And what about Hawkworld, Byrne’s Man of Steel, Pérez’s Wonder Woman Vol. 2 #1, or issues of Secret Origins Vol. 2—essentially any story that contains a big retcon? Could there be seven, eight, or nine distinct Modern Age continuities? Sheesh. While my Modern Age chronology reflects and acknowledges all the retcons associated with Zero Hour and Infinite Crisis and all Superman origin revisions through Superman: Secret Origin, it still regards these stories (and the other aforementioned big retcon tales) as soft reboots, thus negating the need to officially split things into smaller pieces. Other sound minds on the topic—notably Chris J Miller—follow suit.

Continuing with our comics history lesson—another huge reboot occurred in 2011, the largest since the original Crisis. Known as Flashpoint, it functioned similarly to the original Crisis in that, due to a spacetime anomaly (inadvertently created by Barry Allen), all of the DCU’s history was erased and several universes were merged into one single new universe with a shared history. Thus, the Modern Age ended with Flashpoint. Not coincidentally, Flashpoint is the final entry on this Modern Age Batman chronology.

_______________________________

While retcon-laden Crisis events are editorially-mandated and commercially-driven, having more to do with corporate economics and industry politics than storytelling, they needn’t only be viewed through the Late Capitalistic lens of neoliberalism. These huge occurrences, like them or not, each have story potential and can be read as happening naturally in Batman’s life, albeit as naturally as a life led in a completely over-the-top science fiction multiverse could ever hope to be lived. Just as retcons can either ignore history or be intradiegetic (linked to an in-story event), the same thing applies to reboots too. Crisis on Infinite Earths, Zero Hour, and Infinite Crisis each function as intradiegetic occurrences that revise Batman’s past. As omniscient readers, we have the ability to know the complete history of Batman dating back to 1939. To really know Batman’s full history is to read every single issue of every single comic book Batman has ever appeared in, but comic book continuity tells the story of a Batman’s history as he lived it. Comic book continuity isn’t a publication history. It’s a character’s fictional life viewed from their own perspective.

From a complete publication point of view, we’d have one through-line, looking at it this way: Bruce Wayne’s parents are killed; he becomes Batman; with Robin, he clashes with villains like Joker and Penguin; the Dynamic Duo fights in WWII; their adventures get progressively campier; dozens of team-ups and stupendous events transpire; the multiverse is revealed, at which point 1960s Batman is demarcated from his counterpart that debuted in the 1930s (the heroes of yesteryear become the Golden Age heroes of the alternate Earth-2 while their 60s counterparts become the Silver Age heroes of Earth-1); the Crisis occurs in 1985 and all Earths are merged into a single Earth with a new combined/rebooted history; Batman and Robin’s adventures continue with countless more stories, more Crises, and eventually more new iterations of the Dynamic Duo.

From a continuity point of view, we’d place each iteration of character into separate timelines. We have a Golden Age Batman, a Silver Age Batman, and a Modern Age Batman whose history is a more topically relevant mash-up of his prior histories. Modern Age Batman never fought in World War II like Golden Age Batman. Nor did he start in the Swingin’ Sixties like Silver Age Batman. Instead, Modern Age Batman sees the 1980s as his jumping-off point, which makes a lot more sense than him starting in the 1940s or the 1960s. (Naturally, in the future, we’ll see new Batmen that will have later starting points.)

No matter what, publication history and continuity are intrinsically linked. Every time we (the reader) witness the effects of a huge temporal-renovation in comics, the characters are unable to witness those effects because they are inside the story whereas we are outside of it. A character’s perception of a single axiomatic past (i.e. Batman’s career starting in the 1980s) may not match up with the verisimilitude of his actual publication history (i.e. Batman’s comics debut in 1939), but the actual publication history is still relevant to the character’s fictive life in a unique way. Without forty-six years of story leading up to Crisis, we wouldn’t have a Modern Age continuity (or continuities beyond the Modern Age). As the wonderful Greg Burgas explains in his CBR blog, comic book publishers never really throw everything out when they reboot. Instead, they always form the skeletal framework of new continuity out of prior continuity. The Modern Age set the precedent for this, being directly inspired by the urtext of the Golden and Silver/Bronze Ages.

Because the Modern Age is arguably the most scrutinized comic book era, many have tried to build Modern Age timelines online, but a number of these resources are incomplete or just plain incorrect. Therefore, this section of my website is meant to be the ultimate resource for Batman continuity in the Modern Age. As with my Golden Age and Silver Age timelines, my goal is to offer the best and most comprehensive suggested reading order for Batman by applying specific ages to the characters and also specific dates/times to the world in which they exist. Despite the fact that the Modern Age DCU seems to be a virtual reality where the concept of time (and consequently, the concept of age) are soundly rejected, I’ve tried to construct a coherent timeline. If I’ve failed in that endeavor, at the very least, you can simply use my timeline as a reference for the chronological order of Batman’s life sans calendar details.

Before continuing on to the section detailing Bruce’s salad days, please click on the link below to read my Introduction to the “Early Period” of the Modern Age, which is essential in understanding how my Modern Age timeline is set up and how it differs from others.[8] Thanks!

_______________________________

_______________________________

<<< HOME <<< | >>> INTRO TO THE MODERN AGE PART 2 >>>

- [1]COLLIN COLSHER: Some DC higher-ups insist that the Modern Age is actually split into two separate continuities—a pre-Zero Hour timeline and a pre-Flashpoint timeline. I do not subscribe to this concept. More on this below when we discuss Zero Hour.↩

- [2]COLLIN COLSHER: It is important to understand that many of the original Silver/Bronze Age tales that make up the references, occurrences, and reimagined stories within the “Early Period” are intermixed. In other words, there are often Bronze Age stories that wind up in the first eight years and some Silver Age stories that wind up in years nine or ten. Thus, the Modern Age versions of these stories aren’t necessarily married to their previous epochs in terms of definitive boundaries. Let’s not forget that these are reimagined yarns, meaning they have to fit neatly into a new timeline. Essentially, each of the first ten years of the Modern Age timeline attempts to align with a specific range of original publishing years from prior continuities. In other words, Modern Age Year x more-or-less comprises original publications from 19xx through 19xx. But because of narrative nuance and story specificity of each character, while Modern Age Year x must remain static and make sense as a whole, the corresponding 19xx to 19xx which it represents could be different character to character. For example, while my chronology places Batman stories from 1973 through 1981 into Year 9 (and Batman stories from 1981 through 1986 into Bat Year 10), the very same Year 9 could include Flash stories from 1974 to 1980, a slightly different date range. Nevertheless, all characters must ultimately jibe on the same static timeline since all coexist in the same shared universe.↩

- [3]COLLIN COLSHER: There is debate on when Batman’s Silver Age reboot specifically occurs. Some historians start Earth-1 Batman’s chronology beginning in the late 50s while others don’t until around 1960 or even as late as 1964. I’m of the opinion that Batman’s Silver Age transition has a lot to do with the debut of the Justice League of America in 1960 (with a few caveats that push the main Batman title to switch a bit earlier in 1959). For more details about my reasoning, check out the exordium to the Silver Age.↩

- [4]COLLIN COLSHER: The DC Multiverse, in which DC’s primary Universe-0 exists, is a part a larger omniverse. The entire Modern Age comic book omniverse contains a multitude of combined multiverses (such as the DC Multiverse, Marvel Multiverse, Image Multiverse, Dark Horse Multiverse, and Archie Multiverse—in fact, pretty much any publisher of comic books can be said to have its own multiverse including: Oni, Top Shelf, America’s Best Comics, Top Cow, Acclaim, Viz, Boom!, Dynamite, IDW, and many others). That being said, almost everything falls into the realm of the omniverse. In fact, Marvel has even stated in one of its 2004 Handbook issues that DC Comics is a part of the same omniverse as Marvel, further extrapolating, “[The omniverse] includes every single literary [item], television show, movie, urban legend, universe, realm, etc… ever.” Each multiverse in this infinite-seeming omniverse operates with different sets of unique internal universes, planets, planetary systems, characters, and physical laws that generally contrast with (but sometimes only slightly differ from) each other. However, there is always the occasional but rare omniversial crossover—where entire multiverses crossover with each other. Of course, multiversial crossovers are much more common—where alternate universes within a shared multiverse interact.↩

- [5]COLLIN COLSHER: It is also worth re-iterating an important fact: During huge company-wide reboots, it’s not just universes that are being erased, entire timelines associated with each universe are being erased. For example, with Crisis on Infinite Earths, it’s not as if Earth-1 and Earth-2’s timelines simply end with a cataclysm in 1985. If that were the case, then any reference to future tales or stories that occur after 1985 would be null and void. Because the DC multiverse adheres to the laws of determinism, entire timelines are already complete. 1985 is simply the Jonbar point of an event that sucks dry and evaporates the entire Golden Age timeline from the before the Big Bang to the End of Days. And likewise, it wipes the entire Silver Age timeline from its pre-Big Bang to its End of Days. To better understand this concept, we must also adopt a general scientific view of time as another dimension of space—as a where instead of a when. In the case of the original Crisis, 1985 isn’t just a calendar year for our intents and purposes; it is also the point in time (or space-time) where the universe-collapsing anomaly occurs. Furthermore, it is necessary to understand that the event is exactly that, an anomaly (albeit one deliberately started by a villainous force) that ceased to exist on any timeline until its inception. The same system can be applied to Flashpoint in 2011. The Modern Age timeline doesn’t simply end dead in its tracks in 2011. Remember, the entire Modern Age timeline is already complete (from the Dawn of the Gods to the Big Bang to the Big Chill). Flashpoint is merely a space-time anomaly that occurs at the physical point 2011. This anomaly erases the entire Modern Age timeline (past, present, and future), not just the universe. As mentioned before, we should also view reboot erasures less like total obliterations and more like archival processes that close-up or store-away the timeline(s)/universe(s) in question.↩

- [6]KIPFAN / COLLIN COLSHER: While DC didn’t release a “Secret Files 2002” official timeline, we know that DC time-slid Zero Hour from 2000 to 2002 for the following reasons. By the end of the Modern Age, we know definitively that the original Crisis occurred around 1999 (roughly ten years following the debuts of Batman and Barry Allen). We know this due to several in-story factors, but mostly because of Wally West’s given age by 2011 (when the Modern Age ends). As expert chronologist Chris J Miller reasons, “We know that Wally West turned twenty shortly after the events of the Legends crossover (Flash Vol. 2 #1, 1987), and twenty-one during Invasion (Flash Vol. 2 #21, 1988); allowing for proportionate time compression we may conclude that he was nineteen during the Crisis. We also know that he gained his powers and became Kid Flash during the summer he was ten (Secret Origins Vol. 2 Annual #2, 1988, Flash Vol. 2 #62-65, 1992), which (counting back from Year 11) would be summer Year 2, the year after the [debuts of Batman and Barry Allen]—just as we’re told it should be (Life Story of the Flash , 1997). Forward and back, [Wally’s] history matches cleanly with our expanded timescale.” Important items—like Babs being crippled, Jason Todd being killed, Tim Drake becoming Robin, Bane breaking Batman’s back, and Superman dying and returning (just to name a few)—must go in-between the original Crisis and Zero Hour. If the former is set in 1999 by the end of the Modern Age, then it’s clear that the latter can no longer be a mere one year later, as it wouldn’t be able to accommodate the aforementioned important items. (The items would have to be hyper-compressed in a way that wouldn’t make sense.) DC publishers were aware of this as well, and it’s clear that they slid Zero Hour to 2002 at some point before the end of the Modern Age. It’s also worth mentioning that, in terms of specific continuity placement (i.e. anything aside from general order of events), the visual “x years ago” timelines in Zero Hour, Batman Villains Secret Files and Origins #1, Green Lantern Secret Files and Origins #1, and Guide to the DC Universe 2000 Secret Files and Origins #1 are mostly janky and not to be trusted. The Guide to the DC Universe 2000 Secret Files and Origins #1 timeline is particularly a disaster in this regard.↩

- [7]KIPFAN / COLLIN COLSHER: DC released two other visual timelines—in JLA Secret Files and Origins #1 (1997) and Nightwing Secret Files and Origins #1 (1999). These timelines differ from the ones mentioned above in that they are not “x years ago” style timelines. Instead, they refer to events in terms of the JLA and Nightwing’s (respectively) first appearances onward, noting major occurrences in a “Year One, Year Two, Year Three, etc” format. Therefore, these timelines don’t act as time-sliders. Interestingly enough, because of this, the visual timelines in JLA Secret Files and Origins #1 and Nightwing Secret Files and Origins #1 actually bolster the chronology we have built here in certain ways (mostly in terms of order of events). While they aren’t perfect and we still shouldn’t rely on them too much for specific continuity placement, they actually are much more logical than the Zero Hour or Guide to the DC Universe 2000 Secret Files and Origins #1 timelines. It’s also worth mentioning that some of the visual timelines we’ve mentioned above (notably ones in Zero Hour, JSA Secret Files and Origins #1, and DCU Heroes Secret Files and Origins #1, for example) contain history going back long before Superman or Batman’s debuts. And for these older dates, they give year specificity (i.e. 1938, 1940, 1945, etc). These listed years, rooted in the distant past, can be taken as locked-in canon.↩

- [8]COLLIN COLSHER: A linguistic note. When I use the term “salad days” I’m using the original Shakespearean version of the term, which generally refers to a period of time associated with one’s youth (green meaning inexperienced, green linked to salad, etc). However, I’m aware that in the US, the term can also describe “someone’s heyday” or “when a person is/was at the peak of their abilities, while not necessarily a youth.” However, this is a secondary definition, and even in the US, it seems the original definition is more commonly used, hence my use of it that way as well. Most dictionaries define salad days as “a period of your life when you were young and inexperienced” or “a time of youthful inexperience or indiscretion.”↩

Any idea where the Neal Adam’s “Odyssey” should go in the modern age? I realize its’ not a completed story yet but as a story with Dick Grayson as Robin I figured it’d be early. I’d love to get your opinion on its canonicity aswell.

Hi Nabil.

Neal Adam’s “Odyssey” is AWESOMELY INSANE. I love it and if you haven’t read http://www.comicsalliance.com/2011/03/08/batman-odyssey-neal-adams-insane/ you definitely should.

And as always, I’d like to reserve judgments regarding canonicity until after the series is over. However, thus far, I’m leaning toward non-canon since almost everything in the story seems to take place in some uber bizarre Adams-verse. If t were canon (or turns out to be somehow) it would have to be somewhere in late year ten maybe?–if Dick is still Robin and the Al Ghuls are involved.

Have you read Batman: Murder at Wayne Manor?

(http://www.amazon.com/Batman-Murder-Wayne-Interactive-Mysteries/dp/1594742375/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1335125804&sr=8-1)

It retells the origin of Black Mask and was wondering how you felt about it.

I finally read Batman: Murder at Wayne Manor! It’s a very well-written, neatly drawn, and intricately handsome book that I’m sure most Batman fans have overlooked. For all of my readers, if you get a chance to check it out, you definitely should. Unfortunately I don’t think there is a place for this item on the chronology. It takes place 13 months into Batman’s career, but he is shown already sporting the yellow-oval costume. Furthermore, Gordon is never referred to as Commissioner, only as Detective. Plus, I think Black Mask’s debut is a little early for Modern Age Year Two.

Batman & Poison Ivy: Cast Shadows is out-of-continuity mainly because it features an alternative Arkham Asylum that not only looks very different from the Arkham we are used to, but one that is headed by Doctor Wood. This version of Arkham houses inmates such as Joker, Mr. Freeze, Penguin, Catwoman, and Harold the Fly Man (who!?). Obviously, Ann Nocenti and John Van Fleet’s addition of Penguin and Catwoman is their subtle way of telling us this isn’t our normal Modern Age DCU.

Quick question, do you have any websites you recommend in particular that have reading lists for the “high points” as it were of the DCU Modern Age? Having read the Batman stories through, I’d like to do so again at some point, but maybe with a little more context.For example, I don’t want to read every Flash issue along with my Batman reading, but it might be nice to know what storyline he was involved in during, say, “The Long Halloween.”

I don’t know, that might be beyond the scope of what websites are out there. I might end up picking and choosing from some of the trade reading orders, but the creators tend to have their own ideas and besides those tend to lump too many stories into one package, at least for a continuity nut like myself.

Hopefully this makes at least a little sense….. Cheers as always for the awesome work here.

Hi Sam. Definitely makes sense. There isn’t really too much out there. I’d recommend checking out The Unauthorized DCU Chronology, which details EVERYTHING in the Modern Age DCU that is important—although it is incomplete unfortunately, and stops well before “Flashpoint.” Chris J. Miller’s site was obviously a huge influence upon me and reference for me while working on the Modern Age timeline. Sorry I don’t have a better answer, but hope that helps.

–Collin

Hey I was just wondering for the modern age batman what are the primary series of comics that one should read or are you just taking all appearances into account (within the realms of canon anyways)

Was wanting to start collecting modern age batman and just kind of wondering what series you’d start with. I’m considering just going straight through trying to get batman 404-onward in order but thought it’d be interesting to try and collect it in more order of your timeline.

Hi Jake,

My timeline is literally every Batman appearance in chronological order no matter how big or how small. If Batman takes a dump in an issue of Green Lantern, rest assured it will be on my list. (Although Kevin Smith had Batman pee his pants, which I’ve NOT included—but that’s a whole ‘nother can of worms).

The primary Bat books will always (for the most part) be Batman and Detective Comics. Other titles will vary widely in regard to their level of importance to the canon, and it would take a herculean effort to map out which ones are the most valued. But hey, I’ve done that with this very website. And while it might require some blurry eyed late night reading, you can kinda see what’s important and what isn’t by perusing the synopses. Also, http://www.tradereadingorder.com is a good source to see what items were collected in trade (signifying them as more important) in chronological order.

Be aware that after 404-407 (Miller’s “Year One”) there is a ten year gap (the “Year One Era”) before the issues jump back to 401 and continue onward.

Hope that helps a little. Best of luck in your endeavor and be sure to spread the gospel of the Real Batman Chronology Project!

Thank you very much for this information, what I’ll like to know is if “Year one” through “Batman incorporated is what I only need to read to understand the modern age story of Batman ?, and had another question, their is other sections like salad years and post modern era with years 2 and on, are the comics mentioned through each year essential to read to understand the modern era age or do I just read the chronological order above that starts with the laughing man through Batman incorporated ?, thanks

Hi Luis,

The Modern Age consists of comics from 1986 through 2011. Any subsequent sections of the site (i.e. New 52 or Rebirth Era) consist of rebooted continuities that span from 2011 onward. So, to read the full Modern Age Batman chronology, yes, you can read from “Year One” through Batman Incorporated. The Salad Days sections consist of Bruce’s time before becoming Batman, so it’s up to you if you are interested in diving a bit deeper. Hope that helps!

Thanks for the reply, So I don’t need to read anything else besides what’s exactly listed in that chronological reading order of modern age Batman to get a good undetanding of the story ? And I had one more question, you have broken down each of Batman’s years 1 through 23 in the modern age by making references of other issues/comics in each of those, are those issues/comics part of the chronological reading order of modern age Batman as well or they are not ? And if they are, do I need to read them to get a full understanding of the Modern age Batman ?, for examples in year (2) you put Batman legend of the dark knight as a reference but I don’t see it or year (17) part 2 you put green lantern legacy but those are not listed in the chronological order, and that’s what I was I trying to say, are those references mentioned like the ones I just said as examples, do I need to read all those references listed in each year you break down or not ?, thanks a lot for your time and appreciation, sorry for being so detailed, and askin so many questions, just want to get a clear understanding of what I’m going to be reading.

I see what you are saying, Luis. Because you are using my site as a reference for reading order (and especially if you are reading material for the first time), may I suggest only reading the bulleted stories and skipping the reference notes and flashbacks. My site is extremely comprehensive and includes everything chronologically, retroactively folding in the references and flashbacks where they fit onto the timeline. It would be very confusing and jarring to read bits of issues or select pages of trades as you are moving along with your over-arching narrative. So, yeah, good question. To reiterate: skip over the references and flashbacks—you’ll get to that stuff naturally as you read the main action of the issues themselves. Hope that makes sense!

Okay, just to make sure, when you say just to read the bulleted stories, you are saying to only read the titles that are only listed on the chronological order, from the laughing man, all the way through Batman incorporated just how it shows on the footnotes and nothing else, am I correct ?, thanks !

Yes, I’d suggest only reading non-reference listings and non-flashback listings in chronological order. I’m not sure what “The Laughing Man” you’re referring to as a starting point is (maybe “The Man Who Laughs”?), but the Modern Age runs from Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight #1 (“Shaman Part 1”) through Batman Incorporated Vol. 2 / Convergence / Flashpoint.

Yes I was referring to “the man who laughs” as the starting point like how it shows on the chronogical order, but now your saying that the modern era starts with legends of the dark knight “shaman”, so what is the starting point ?, I’m confused, I have never read a comic in my life, so I’m new to this, I’m sorry for the many questions, thanks !

“The Man Who Laughs” is in Year One for sure, but it’s certainly not the first story. It is listed as number 9 on my timeline. Still not sure what you are looking at, sorry!

But anyway, if you are new to reading comics and want to read Batman chronologically, I’d start by reading Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One before all else. It’s one of the best ever written and the ultimate starting point—all the other Year One stories orbit around it. Basically, I’d start by reading Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One AND THEN begin using my timeline as a reference after that.

So do I just follow this exact list that was just updated and I’m good to go ? Nothing else besides what’s on this list, am I correct ?, Do I have to read each of the comics/issues that are refrenced or read notes/summaries that you right in each year in order to understand what exactly is going on ? Or like I said just read exactly what’s on that list that you just updated and ignore everything else ?, thanks again !

You could read hundreds of canonical Batman stories if you really wanted to, but as a new reader I suggest simply going with that simplified “essential” trade list. If you have any questions along the way, shoot me an e-mail at ccolsher@gmail.com.

Thank you very much, you have been very helpful, would that essential list cover all I need to know to have a good understanding of the modern age Batman story ?, you have written paragaraphs of summaries and anaylising each Batman year from 1-23, do I have to read those paragraphs you wrote in each year, for example you put “1.A the shaman part 1” and then you write a paragraph and you go to “2.A Batman Year one” and then you write a paragraph and so forth, do I need to read those things as I go through comics I’m going to start reading or not ?, maybe I asked you this already, I’ve asked so many questions, very sorry once again, just want to make sure, thanks !

Don’t overcomplicate things, Luis. That’s my job! 😉 There are a thousand ways to interact with and engage with serialized storytelling—and none of them are wrong. One doesn’t necessarily need anything in order to understand narrative and continuity. As I said, and I’ll stick to it, I think your best bet—as a new reader—is to skip the nitty gritty that my website has to offer (for now). Reading from the “essential” trade paperback list will be a much more enjoyable endeavor. Only afterward would I then go back and check out the details of my chronology. Hope I’ve been clear, and I hope you enjoy your foray into the mixed-up world of superhero comics.

Hi Collin, I just read Year one, I know Monster men, and then, prey, the mad monk, come next, but those stories don’t seem that entertaining, can I just skip to the man who laughs ? Or would I miss important things ?, thanks !

The trade list that is up contains stories that are pretty much all over the place in terms of content and quality—HOPEFULLY most of it is, at the very least, entertaining! It’s really up to you, though, Luis!

Realize that you are asking a guy that literally read every single Batman-appearing floppy issue the Modern Age had to offer—from Crisis and Scare Tactics to Superman and Batman vs Aliens and Predator and Flashpoint (and everything else in-between). Any list I’ve pared down is a feat in and of itself. If you read a synopsis and it seems like a pass, then pass! You can always go back later. I doubt there’s anything that you could skip and be really truly confused about.

Hi Collin! First of all thank your very much for the great work you’re doing!

I tried to read(/buy) all the comics (except flashbacks / reference) from years 1 – 10 and now (stuck somewhere year 6) i’m beginning to realise that i won’t be able to do so for the whole modern era… So i’m looking for a extended essentials list… i have seen your note on this page but i’m looking for an “extended” version 🙂

I have searched the net for something like that but in the end i always came back here…

I’m not asking you to “make” a new list (i think you have enough TODO’s already), but maybe such a list has already been made by somebody?

Cheers and thank you again!

Thanks for the love, Pita!

By far THE MOST requests I get are to make a complete trade paperback list. I’ve gotten so many, in fact, that I think I can’t ignore it. The people have spoken!

However, such a list coming from me probably won’t realistically be assembled for quite some time, so don’t hold your breath. In the meantime, Trade Reading Order and Collected Editions are fantastic resources.

Here’s what I’ve got so far in terms of his love interests/sex life on this timeline, I’m probably missing some:

YEAR ONE

-Viveca Beausoleil (The Batman Chronicles #19)

-Julie Madison. (Batman and the Monster Men, Batman and the Mad Monk, Batman #682, The Batman Files)

-Theodora Hackley (Date in LOTDK #2)

-The shaman’s granddaughter (*Platonic) (LOTDK #1, LOTDK #5)

-Selina Kyle (Sexual tension as Batman and Catwoman)

YEAR TWO

-Linda Page (The Batman Files)

-Dates Selina Kyle (Long Halloween, The Batman Files)

-Summer Skye Diamonds (Journey into Knight)

-Jillian Maxwell (The Batman Files, Legends of the Dark Knight Halloween Special #1)

-Pamela Isley? Sort-of platonic* (Hot House LOTDK #42-#43)

-Girl that Bruce Wayne would have married if his parents hadn’t died. (LOTDK #76-#78)

-Dr. Lynn Eagles (LOTDK #65)

YEAR THREE

-Dr. Lynn Eagles (LOTDK #66-#68)

-Dinah Laurel Lance? (The Batman Files)

-Unnamed date from Batman Ego.

-Keeps dating Selina Kyle for the whole year, so supposedly very serious about it, tho in Batman #600 he rejects her advances to be more serious so perhaps he was still in the playboy lifestyle from time to time, unless she meant she wanted to marry him. (Long Halloween)

YEAR FOUR

YEAR FIVE

-Keeps dating Selina Kyle, he must really like her! (Long Halloween, Dark Victory)

YEAR SIX

-Selina and Bruce breakup. (Batman: Dark Victory #5)

-Callie Dean (*Platonic) (Batman Confidential #40-#43)

-Date that went with Bruce Wayne and Alfred to Haly’s Circus (Batman #436)

-Supermodel Britanny St. James (Robin Annual #4)

-Selina and Bruce may have broken up but Batman and Catwoman still have a ton of sexual tension when they meet each other (Batman #683, Batman Incorporated #1, The Batman Files)

-April Clarkson (Gotham after Midnight)

YEAR SEVEN

-Kelli (JLA 80-Page Giant #2)

-Still does everything shy of having sex on rooftops with Catwoman (And for all we know he does that, The Batman Chronicles #9)

-Kathy Webb/Original Batwoman (Batman Incorporated #4, Batman #682, The Batman Files)

YEAR EIGHT

-Breaks up with Kathy. (Batman #4)

-Breaks the heart of an unnamed girl in Batman Ego.

-Still flirts with Catwoman. (Catwoman: Defiant)

YEAR NINE

-Silver St. Cloud (Detective Comics #469-#479, LOTDK #132-#136)

-Talia al Ghul (Saga of Ra’s Al Ghul, Batman #330-#331)

YEAR TEN

-Marries Talia al Ghul and impregnates her (Batman: Son of the Demon)

-Natasha Knight (The Batman Files)

YEAR ELEVEN

-Catwoman (Detective Comics #569-#570)

-Goes on a date with Vicki Vale, I guess we can assume she’s on a sorts of friends with benefits situation with him (Batman #402-#403)

YEAR TWELVE

-It’s probably the worst year of Batman’s life. The Killing Joke and Death in the Family happens. As far as I can tell, he doesn’t date anyone in this year, not that we know of anyway, after all most modern Batman stories barely explore Bruce Wayne so it’s possible he had some off-screen flings, but definitely nothing serious. I’d apply this same note to pretty much every other year, actually, after all, Bruce has to keep up that playboy persona rolling.

With early years Batman stuff, I assume they felt more inclined to introduce all sorts of romantic subplots because it was just him, Alfred and a couple rogues, but now that Bruce is dealing with a ridiculously large rogues gallery, has a bunch of superhero allies, and has an extensive Bat-Family, there is much less time to focus on that stuff, doesn’t mean Bruce doesn’t date/sleep around but we never see these dates, or if we do, they’re unnamed and we don’t know them.

YEAR THIRTEEN

-He starts to date Vicki Vale in a more serious manner. (Gotham Gazette Batman Alive? #1, Batman #475, Detective Comics #642, Batman #746)

YEAR FOURTEEN

-Shondra Kinsolvig (Knightfall)

Nice start here, Jack! LOTDK #86–88 also features Batman having a rare one night stand. I never added it to the timeline because it felt like one of those out-of-continuity LOTDK arcs. Been meaning to give it a re-read but haven’t had the time.

Finished it! Probably missed some, but:

YEAR ONE

-Viveca Beausoleil (The Batman Chronicles #19)

-Julie Madison. (Batman and the Monster Men, Batman and the Mad Monk, Batman #682, The Batman Files)

-Theodora Hackley (Date in LOTDK #2)

-The shaman’s granddaughter (*Platonic) (LOTDK #1, LOTDK #5)

-Selina Kyle (Sexual tension as Batman and Catwoman)

YEAR TWO

-Linda Page (The Batman Files)

-Dates Selina Kyle (Long Halloween, The Batman Files)

-Summer Skye Diamonds (Journey into Knight)

-Jillian Maxwell (The Batman Files, Legends of the Dark Knight Halloween Special #1)

-Pamela Isley? Sort-of platonic* (Hot House LOTDK #42-#43)

-Girl that Bruce Wayne would have married if his parents hadn’t died. (LOTDK #76-#78)

-Dr. Lynn Eagles (LOTDK #65)

YEAR THREE

-Dr. Lynn Eagles (LOTDK #66-#68)

-Dinah Laurel Lance? (The Batman Files)

-Unnamed date from Batman Ego.

-Keeps dating Selina Kyle for the whole year, so supposedly very serious about it, tho in Batman #600 he rejects her advances to be more serious so perhaps he was still in the playboy lifestyle from time to time, unless she meant she wanted to marry him. (Long Halloween)

YEAR FOUR

YEAR FIVE

-Keeps dating Selina Kyle, he must really like her! (Long Halloween, Dark Victory)

-Rachel Caspian (Batman Year Two)

YEAR SIX

-Selina and Bruce breakup. (Batman: Dark Victory #5)

-Callie Dean (*Platonic) (Batman Confidential #40-#43)

-Date that went with Bruce Wayne and Alfred to Haly’s Circus (Batman #436)

-Supermodel Britanny St. James (Robin Annual #4)

-Selina and Bruce may have broken up but Batman and Catwoman still have a ton of sexual tension when they meet each other (Batman #683, Batman Incorporated #1, The Batman Files)

-April Clarkson (Gotham after Midnight)

YEAR SEVEN

-Kelli (JLA 80-Page Giant #2)

-Still does everything shy of having sex on rooftops with Catwoman (And for all we know he does that, The Batman Chronicles #9)

-Kathy Webb/Original Batwoman (Batman Incorporated #4, Batman #682, The Batman Files)

YEAR EIGHT

-Breaks up with Kathy. (Batman Inc. #4)

-Breaks the heart of an unnamed girl in Batman Ego.

-Still flirts with Catwoman. (Catwoman: Defiant)

YEAR NINE

-Silver St. Cloud (Detective Comics #469-#479, LOTDK #132-#136)

-Talia al Ghul (Saga of Ra’s Al Ghul, Batman #330-#331)

YEAR TEN

-Marries Talia al Ghul and impregnates her (Batman: Son of the Demon)

-Natasha Knight (The Batman Files)

YEAR ELEVEN

-Catwoman (Detective Comics #569-#570)

-Goes on a date with Vicki Vale, I guess we can assume she’s on a sorts of friends with benefits situation with him (Batman #402-#403)

YEAR TWELVE

-It’s probably the worst year of Batman’s life. The Killing Joke and Death in the Family happens. As far as I can tell, he doesn’t date anyone in this year, not that we know of anyway, after all most modern Batman stories barely explore Bruce Wayne so it’s possible he had some off-screen flings, but definitely nothing serious. I’d apply this same note to pretty much every other year, actually, after all, Bruce has to keep up that playboy persona rolling.

With early years Batman stuff, I assume they felt more inclined to introduce all sorts of romantic subplots because it was just him, Alfred and a couple rogues, but now that Bruce is dealing with a ridiculously large rogues gallery, has a bunch of superhero allies, and has an extensive Bat-Family, there is much less time to focus on that stuff, doesn’t mean Bruce doesn’t date/sleep around but we never see these dates, or if we do, they’re unnamed and we don’t know them.

YEAR THIRTEEN

-He starts to date Vicki Vale in a more serious manner. (Gotham Gazette Batman Alive? #1, Batman #475, Detective Comics #642, Batman #746)

YEAR FOURTEEN

-Shondra Kinsolvig (Knightfall)

YEAR FIFTEEN

-Vesper Fairchild (Batman #540-#541, The Spectre Vol.3 #51, Batman #544-#546, Batman #600)

-Yuko Yagi (Batman: Chilld of Dreams)

YEAR SIXTEEN

-Spends a sad night with Talia who takes care of him (No Man’s Land #0)

-I guess the implication is that he’s still dating Vesper?

-I’d have to check but JLA #47-#54 implies he’s still dating around in the playboy lifestyle. Either way this is a super intense year for Batman, with No Man’s Land and Tower of Babel.

YEAR SEVENTEEN

-Develops a platonic liking to Sasha Beardoux, his bodyguard. He won’t reveal it to her until the end of Bruce Wayne: Murderer? in Detective Comics #775

She’s also deep in love with him.

-He’s still dating Vesper, until he breaks up with her in the most cold way possible, by inviting her while hanging out with a bunch of girls with which he’s playing Marco Polo, this is also another hint that while we may not see it, Bruce is very much keeping the playboy persona alive in more casual relationships. (Detective Comics #764)

YEAR EIGHTEEN

-We don’t see him dating anyone this year as far as I’m aware. Intense year with Bruce Wayne Murderer?, still the intense discussion between Sasha and Bruce occurs this year.

YEAR NINETEEN

-Wonder Woman (The Obsidian Age) (JLA #90-100)

-Enters a serious relationship with Catwoman again, although their relationship is intense they break-up, although they still date and have sex ocassionally after that (Hush) (Catwoman Vol. 3 #32)

YEAR TWENTY

-Kisses Black Canary (Birds of Prey #90)

-He kisses Sasha Beardoux (The OMAC Project #1-#3)

-He still ocassionally has sex with Catwoman (Catwoman vol. 3 #39)

YEAR TWENTY-ONE

-Dates Karrie Bishop (Detective Comics #822)

-Lilith Rutledge (LOTDK #207-#211 “Darker than Death)

-Zatanna. (Detective Comics #833-#834)

-Kay Scott (Detective Comics #835-#836)

-Bekka (Superman/Batman #37-#42)

-Jezebel Jet, and hints of Bruce still living that playboy lifestyle off-screen (Batman #655-#658)

YEAR TWENTY-TWO

-Jezebel Jet (Batman RIP)

-Una Nemo (Batman and Robin #18)

-Annie (Return of Bruce Wayne #2, he actually technically dates her in 1640 but whatever)

YEAR TWENTY-THREE

-Marsha Lammar (Return of Bruce Wayne #6, again, he technically dates her in 1971 but whatever)

-Still has sex and romantic encounters with Selina Kyle (House of Hush, Batman Inc., Batman 80 Page Giant 2011 #1)

-Dawn Golden (The Dark Knight #1-#5)

-Is heartbroken by Talia’s evil ways, kisses her while Gotham is on fire (Batman Inc. #11-#13)

Overall, his list of love interests in the modern age would be: Viveca Beausoleil, Julie Madison, Theodora Hackley, Shamans Granddaughter, Selina Kyle, Linda Page, Summer Skye Diammonds, Jillian Maxwell, Pamela Isley, Dr. Lynn Eagles, Dinah Laurel Lance, date from Ego, Rachel Caspian, Callie Dean, Britanny St. James, April Clarkson, Kelli, Kathy Webb, unnamed girl from Ego, Silver St. Cloud, Talia Al Ghul, Natasha Knight, Vicki Vale, Shondra Kinsolvig, Vesper Fairchild, Yuko Yagi, Sasha Beardoux, Wonder Woman, Karrie Bishop, , Lilith Rutledge, Zatanna, Kay Scott, Bekka, Jezebel Jet, Una Namo, Annie, Marsha Lammar, Dawn Golden.

His most important loves would be: Julie Madison, Selina Kyle, Rachel Caspian, Kathy Webb, Silver St. Cloud, Talia Al Ghul, Vicki Vale, Shondra Kinsolvig, Sasha Beardoux, and Dawn Golden. He’s been engaged with Julie, Rachel, Kathy, Talia about to propose to Shondra.

Thanks and will do! I should also add Lois Lane to that list, as Hush kinda implies there was something between the two at some point, not sure in what year tho haha

Hey Collin, huge fan of your site I only recently discovered it and it’s helped a lot. One modern age story I don’t see discussed by anyone, pretty much at all, is Teen Titans: Year One written in 2008. I’m compiling a modern age timeline of Batman, the bat family, and some JLA members and I would really like to include the story of Dick and his fellow titans coming together for the first time. I’m just not sure if it’s canon, or if it is, where to place it in regards to stories like Robin: Year One, Batgirl: Year One or JLA: Year One. I also would like to include stories like the Judas Contract but since they are pre crisis, I’m not sure if it fits or not, I think Nightwing: Year One might have replaced it to some extent.

Would love some insight, thanks!

Hi Santi! I have Teen Titans Year One in Year Eight. Some folks might place it earlier, but my timeline is a little different than some other timelines out there. In any case, I have Robin Year One, Batgirl Year One, and JLA Year One all prior to Teen Titans Year One, spread out through Year Six and Year Seven.

And Judas Contract is referenced in Countdown #36, so it’s definitely canon in the Modern Age. I have it in Year Ten, in-between chapters of “Nightwing Year One.”

Awesome thank you so much! I always thought Teen Titans: Year One came before Batgirl: Year One because of the Titans reference in that story but I understand that lots of Batgirl: Year One isn’t technically considered canon.

Also, glad to know that Judas Contract is canon, I assume the same can be said for Tales of the Demon? I haven’t read that one yet but I’m wondering if that’s Ra’s al Ghul’s first meeting with Batman in the modern continuity or if they meet for the first time in the Matt Wagner Trinity issues (which I recently ordered but haven’t read yet).

Yeah, the first 3-4 issues of Batgirl: Year One don’t jibe with anything else for multiple reasons, so I’ve always considered them to be non canon. Tales of the Demon is a trade collection of Silver Age comics—Detective Comics #411, #485, and #489-490; Batman #232, #235, #240, and #242-244; and DC Special Series #15.

The Modern Age version of the Saga of Ra’s al Ghul is a bit more abridged, featuring approximations of Detective Comics #411, Batman #232, Batman #235, Batman #240, and Batman #243-245. Kathy Kane’s death (Detective Comics #485) is also referenced in the Modern Age.

Many of auteur creator Matt Wagner’s works tend to occupy their own canon space. Such is the case with Trinity (and his LOTDK “Faces” arc). Ra’s al Ghul’s first appearance in the Modern Age still reflects his original appearances in the Silver Age i.e. the abridged Tales of the Demon still stands as canon. Trinity steps all over this by giving us an alternate Ra’s al Ghul debut, which is one of but only a handful of reasons it’s non-canon. Other reasons follow: It shows an alternate depiction of Batman’s first meeting with Wonder Woman, shows Batman wearing bizarre armor not shown in any other comic, and contradicts several Infinite Crisis continuity changes, including the fact that the Big Three first meet when fighting the Appelaxians right before forming the JLA.

Oh wow, totally wouldn’t have noticed that Trinity and especially Faces didn’t fit into the modern continuity, kind of unfortunate considering how big a fan I am of the way he draws Batman but at least Monster Men and Mad Monk tie in together nicely with Year One. Thanks so much for the clarification on these comics Collin, it really makes mapping the early years of the modern timeline a lot easier. Looking forward reading Judas Contract and Tales of the Demon, everything pre crisis is very new to me.

Hey Collin, I gotta ask, where would Secret Six Vol. 3 #1 and #2 take place? In that comic we see a fight between Batman and Catman, and we also see Batman interacting with Huntress, I can’t seem to find it on the timeline. Thanks.

I missed that one! Adding it now into Year 22 Part 1. Thanks!

Where would the flashbacks/events from Legends of the Dark Knight #94 be placed on the modern age timeline? In particular, the stuff involving The Bulb and Age O’Quarious

Hey Anthony, I wouldn’t place them since that issue is undoubtedly non-canon. But if you were to include that “1952 flashback” then it’d go around other story flashbacks and/or references of that era.

Would it be possible for that story to fit in the golden age or silver age timelines?

For something written/published in 1997, I would never do it, and that’s a fairly hard rule for me. Legends of the Dark Knight, dubious canonically in its own era, has zero to do with prior continuity. But as I say, continuity is personal, so if you think it works for your headcanon, go for it.

Sorry, but I would also like to inquire if the story Illusions by Alan Grant (from Batman: Shadow of the Bat #65-67) is considered canon? As well as “Madmen Across the Water” from Showcase ‘94 #3-4. I feel the latter in particular could fit somewhere on the modern age timeline

SOTB #65-67 is already on my timeline in Year 15. And it looks like my reference note about Dr. Faustus from Showcase ’94 got deleted somehow, so I will re-add it. Thanks for pointing that out! Notably, all SOTB and Showcase issues are canon.