INTRO TO THE MODERN AGE PART 2

_______________________________

HOW MY TIMELINE IS STRUCTURED

Much of the information in the Modern Age section of the Batman Chronology Project was directly influenced by the unbelievably amazing “Unauthorized Chronology of the DC Universe” by Chris J Miller. The domain registration has lapsed on Miller’s site, originally at dcu.smartmemes.com, but you can still check out his unfinished but inspirational historiography via the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. If you haven’t seen this site, then you aren’t a true continuity buff or worthy of the title “comic book nerd.” I encourage everyone to check out this herculean effort! Like myself, Miller regards canonical narrative the way it is written (post retcons, of course). His timeline also mirrors mine in length, around twenty-three years long, based upon information taken directly from within comic books. If you literally read every Modern Age Batman comic book from 1986 through 2011, noting all the changes of season, topical references, references to time, editorial notes, character aging, and character development, you wind up with a mix of contradictions. But if you whittle that down to form the best possible combination of these contradictions, you’ll be able to find a (semi-)concrete timeline. This is essentially what Miller and I both have done.

However, I’d be remiss if I didn’t explain why my chronology explicitly (and purposefully) differs from other chronologies on the web, including Miller’s “Unauthorized Chronology.” First off, when you add-in all the other DC characters (besides the Bat-Family) you’ll find that things need to shift and fit-to-form even more in order to make things understandable and explicable from a narrative perspective. This is Miller’s burden, one which I haven’t quite undertaken—and one that has caused some contradiction between our works. Miller’s chronology, along with some other respected online timeline projects, also place important events (such as the debut of Two-Face, the appearance of Dick Grayson as Robin, and the formation of the JLA) a year or so prior to when they appear on my list. For example, Miller has Two-Face debuting in Year Two and Robin debuting in Year Three shortly after the JLA. My chronology lists Two-Face debuting in Year Three and Robin debuting in Year Five before the JLA debuts.

The Batman Chronology Project mainly differs because it does not compress, shorten, or exclude The Long Halloween or Dark Victory. The Long Halloween is the ultimate and final origin story for Two-Face. Likewise, its sequel Dark Victory is the ultimate and final origin story for Robin. (Robin: Year One was published a year after Dark Victory, but it actually takes place after Robin’s debut in Dark Victory, co-existing alongside it fairly well.) The only way to have Two-Face debut in Year Two is to retcon a shorter Long Halloween. The only way to have Robin debut in Year Three is to basically chisel the entirety of the yearlong Dark Victory series into mere weeks. And the only way to have the JLA debut in Year Three is to already have eliminated the three years necessary to house The Long Halloween and Dark Victory. Furthermore, one would probably need to eliminate many of the Legends of the Dark Knight stories that I refuse to exclude from my timeline to get to a universe where Two-Face, Robin, and the JLA debut earlier.

One could pitch an argument that compromise (retconning/time-compression) is necessary in order to jibe with DC editorial and these other Modern Age timelines, especially since the Batman Chronology Project time-compresses many arcs in Modern Age Batman’s later years, especially after Year 14. I am against that argument, however, because the temporal tightening that goes on in the latter end of the timeline doesn’t alter narrative or change in-story details (except in quite rare unavoidable cases). The majority of the time-compression happens simply via the elimination of gaps and ellipses (i.e. breathing room) in-between stories. Most topical references have to be ignored as a result of this compression, but narrative isn’t erased or changed wholesale.

Another reason to go against retconning/shortening The Long Halloween and Dark Victory is that these titles are limited series that take place in Batman’s past. Written and published with 20/20 hindsight, they are retroactively fitted into the timeline AS OPPOSED TO already in existence on the timeline and then retroactively changed. Stories like The Long Halloween and Dark Victory mirror Frank Miller’s “Year One” in the sense that they are NOT malleable and function with SPECIFICITY. On the opposite end of the spectrum from these flashback limited series lie the average ongoing monthly issues, which are more prone to being affected by time-compression and retcons due to the tricky nature of long-form serialized storytelling by multiple creators. Monthlies tend to contradict other monthlies because there are a ton of different creators and editors working hand-in-hand to build an entire multiverse in relative real-time. This makes it so that the contradictory-prone monthlies can only align correctly (or be aligned correctly) by retconning their narratives to fit neatly into a timeline—but only after one can gather all the pertinent puzzle pieces of the universal line, which means only after a lengthy time has passed since initial publication.

I can’t speak for the various opposing chronologies out there, nor can I speak for DC itself, but I can quote from Miller’s website notes to explain his mindset, which surely reflects the mindsets of those who disagree with my opinions. By laying out Miller’s timeline-building blueprint, I can compare and contrast my own architecture to his, which gives a better overall idea as to why our timelines don’t sync-up. To start, Miller puts the debut of Two-Face and the first appearance of Robin earlier in order to match his timeline as closely as possible to what DC probably had in mind. He also gives credence to Batman Annual #14 (entitled “Eye of the Beholder”) as the legit origin for Two-Face and credence to “Batman: Year Three” flashbacks (from Batman #437) as the legit origin of Dick becoming Robin. To quote Miller: “Superficial differences (in dialogue, etc.) notwithstanding, a close look at the details reveals that The Long Halloween story is clearly meant to expand upon the [shorter] Batman Annual #14, not supersede it. However, note that the internal timeline of Long Halloween cannot be fully reconciled with other known events, as it would delay Two-Face’s debut until late Year Three—while its sequel, Batman: Dark Victory, would push Robin’s debut all the way to Year Five.”

While Miller—and a lot of other folks—believe that both stories co-exist together as they were originally published (without much or any alteration), that is just not possible. While the opening part of Batman Annual #14 (the Rudolph Klemper bit) has been canonized via Matthew Manning’s The Batman Files, occurring immediately before the start of The Long Halloween, The Long Halloween IS meant to supersede Batman Annual #14, which means, as Miller fears, Two-Face’s debut is indeed pushed back to Year Three. Likewise, Miller laments the fact that, if The Long Halloween is to be taken as unaltered gospel (which is how I have basically taken it), Robin’s debut gets pushed back to Year Five. On my timeline Robin’s debut does indeed occur in Year Five.

Miller slight goes even further in relation to Dark Victory. His caveat: “If most of the [Dark Victory]’s specific holiday references are disregarded, and the crimes depicted are read as merely holiday-themed, the timeframe can be compressed.” Because of this sentiment, Miller retcons Dark Victory from a full year down to a few weeks, making it so that the Hangman (Sofia Falcone Gigante) doesn’t kill on holidays, but merely is a holiday-themed killer. This is a huge liberty that Miller takes to make his timeline work—one which I am unwilling to do.

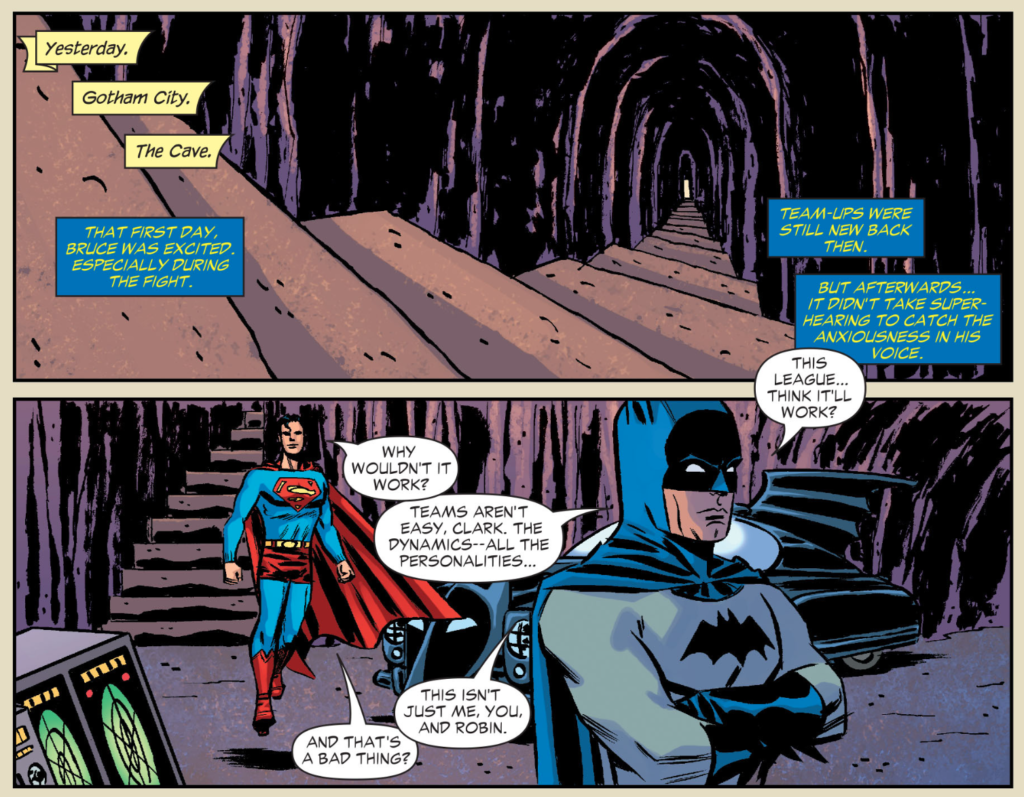

In regard to Miller’s early placement of the JLA debut, it would seem that he regards JLA: Year One as canon primarily because the “origin” piece in the second feature to 52 #51 shows a flashback to JLA: Year One, specifically an image of Batman, Superman, Wonder Woman, Aquaman, Green Lantern, Martian Manhunter, Flash, and Black Canary fighting the Appelaxians. This “JLA origin” also says that the founding trio doesn’t join full-time until later. Miller’s timeline canonizes both JLA: Year One and a seminal flashback scene from Justice League of America Vol. 2 #0, which is fine. However, I take issue with Miller’s following rationalization: “[The JLofA v.2 #0 flashback scene depicting the Big Three forming the JLA] is a notable change to ‘New Earth’ history as compared to post-Crisis canon. The relevant flashback scene seemingly implies that it takes place in the immediate aftermath of the founding battle with the Appellaxians, but a reference to Robin precludes a date earlier than this. The origin recap in [the second feature to] 52 #51 confirms the delay as well.” While a “delay” it does indeed confirm, we are not specifically told that the delay is a full-year delay due to JLA: Year One. In fact, I’d argue against that, especially since JLA: Year One‘s narrative doesn’t even span a full calendar year. Also, the flashback from JLofA Vol. 2 #0 clearly reads as if it is occurring very shortly after the Appelaxian affair (as opposed to a full year or even months later). The reference to Robin in JLofA Vol. 2 #0 solidifies the idea that the Appelaxian affair has to happen after the Boy Wonder’s official debut (and after he has met Superman). This fact is not reflected in Miller’s chronology, which goes against the simplest answer by having Robin debut after the Appelaxian attack.

In summation, Miller’s chronology significantly alters both The Long Halloween and Dark Victory by mega-compressing them both into extremely shortened versions—and, in the case of the latter, nearly erasing it entirely. Miller also regards the formation of the JLA differently, misinterpreting flashback references related to it. But Miller isn’t alone. There are plenty of scholars and comics journalists that have followed his path. How can various timelines be so perfect (tooting my own horn here, sorry) and yet so opposing? It’s frustrating, but it boils down to a simple difference of opinion. My take dictates the direction and scope of my chronology while giving it validity. Could I be wrong? Like I always say, there’s no real answer. Luckily, aside from these three key areas—the Two-Face, Robin, and JLA debuts—the Batman Chronology Project links-up pretty squarely with most other timelines, including Miller’s, in every other way.

___________________

________________________________________________________________________

DC’s BROKEN TIMELINE?

My Modern Age timeline not only differs from DC’s “official” Modern Age timeline because of my strict (more literal) reading of Long Halloween and Dark Victory, but also because, unlike DC publishers, I view Zero Hour as a soft reboot (as opposed to a hard reboot). This means that, while both DC’s timeline and my timeline are hyper-compressed, DC’s is actually way more compressed than mine. As such, age references to many of the characters don’t jibe with my timeline, requiring fanwanks and caveats. A big example of this can be seen with Tim Drake, who is forced to debut as Robin a bit younger than he is said to have in the comics.

Some folks will say, if DC has an “official” Modern Age timeline, shouldn’t be bow down to that as canon? Those folks should keep in mind that, even the DC “official” version of things, like my chronology, must also be created or fabricated. (There’s a reason why I use quotes around the word official.) There really can be no definitive history that can be taken as gospel, especially since any chronology must constantly shift to meet the never-aging lineaments attributed to the characters within its fiction. Thus, the complicated multiplication of chimeras in relation to Batman continues. (You’d be hard-pressed to find two DC writers adhering to the same exact timeline, even under the company’s supposedly strict editorial umbrella.)

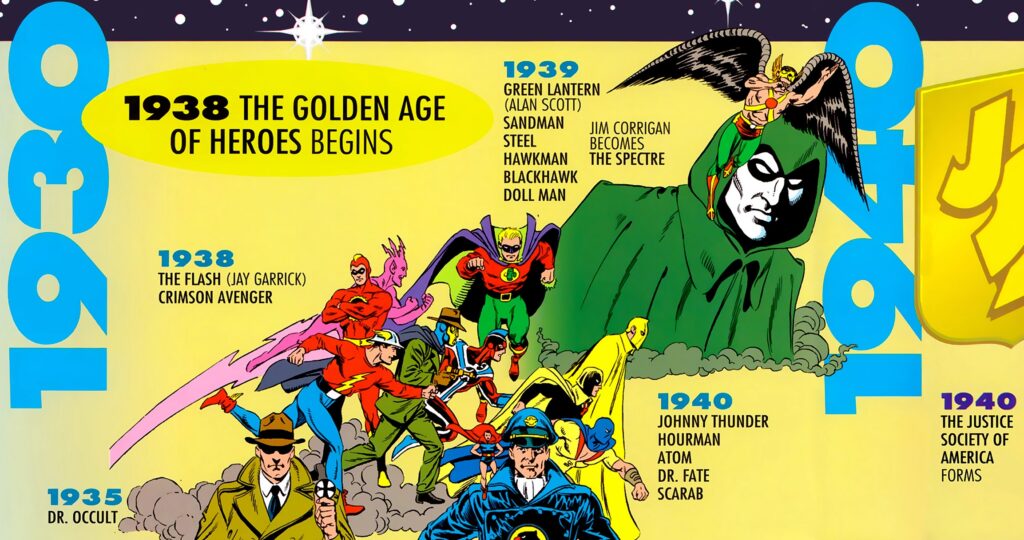

If we look back to the tail end of the Golden Age and the bulk of the Silver/Bronze Age, DC publishers started to contradict their own timeline for fear that their characters were getting too old or stagnant. The same thing happens in the late Modern Age where you start getting a proliferation of editorial tags and bogus time references—an attempt to stave off the eventual need to hit the restart button entirely. The Modern Age DCU chugs along in relative real-time for about fifteen to twenty years and then all of a sudden time seems to stand still (even though events keep on happening and characters keep on living their complicated little lives).

Sliding-time and retroactive compression cannot be denied when building the Modern Age timeline, but there is an argument as to how compressed the timeline should be. DC publishers have needlessly over-shrunk, compressed to a fault. This brings up one of the two major differences between my chronology and DC’s—the interpretation of Zero Hour. Many DC higher-ups consider the Modern Age timeline to consist of two separate continuities: a “pre-Zero Hour timeline” and a pre-Flashpoint timeline.” With this consideration, earlier stories noticeably change from beefy texts overstuffed with data into highly-compressed reference materials. Anything pre-Zero Hour not only loses substance, but also gets cast into the distant void of its own separate chronology.

When I constructed my timeline, I did so moving forward, building what seemed like a correct chronological listing of stories. To create a timeline that DC seems to utilize, we almost have to work backward, looking at the latest possible references to ages (i.e. how old did DC say their characters were at the bitter end of the Modern Age) and how many “years ago” flashbacks in the later issues imply. These are the final clues in the Modern Age that tell us roughly how many years the Caped Crusader has been crusading. Here are a few important ones (according to DC). Tim is 17-years-old going on 18 (Red Robin in 2011). Bruce is possibly nearing forty-years-old (said to be in his thirties in Batman RIP). Bruce met Silver St. Cloud nearly 10-years-ago (using Widening Gyre by Kevin Smith as a reference since it came out in 2010-2011 despite the fact that it is non-canon). There are many more, but these tidbits from three major 2011 story-arcs give us a pretty decent idea that Batman at the end of the Modern Age, according to DC, was around his 14th or 15th year in costume. Below is a quick list. I will refer to my chronological listings as BY1 for Bat Year One, BY2 for Bat Year Two, etc…

___________________

DC YEAR ONE: Frank Miller’s “Year One” still holds tried-and-true. Thankfully the horrible addition of Batman peeing his pants (thanks Kevin Smith) isn’t canon. Therefore, DC Y1 is almost exactly the same as my BY1.

DC YEAR TWO: As site contributor/fellow Batmanologist Valheru states, DC Y2 comprises many stories referenced from the Kane/Finger era (i.e origins of most of Batman’s rogues gallery). The Long Halloween and “Batman: Year Two” go here. BY2 through BY3 is comprised mostly of these rogues gallery debuts and LOTDK tales. Many of the LOTDK stories just aren’t canon anymore according to DC. (Or if they are, they are compressed into near oblivion and all placed into DC Y2.) My BY2 is basically the same as DC Y2, also including “Batman: Year Two” and the start of The Long Halloween.

DC YEAR THREE: Dark Victory and “Venom” occur. Dick Grayson debuts as Robin at age 13. The JLA debuts here. (Timelines in Zero Hour, Batman Secret Files and Origins, Villains Secret Files and Origins, Nightwing Secret Files and Origins, and Guide to the DCU 2000 all list Dick debuting as Robin in DC Y3.) DC Y3 is basically my BY3 through BY6.

DC YEAR FOUR: This year comprises many Batman and Robin stories referenced from the late Golden Age (think “pop-crime”). DC Y4 is comprised of large chunks of my BY6 and BY7, which contain story references mostly from 1960 through 1967.[1]

DC YEAR FIVE: This year comprises Batman and Robin stories referenced from the late Golden Age (early to mid 1960s), but also begins the transition into the Silver Age (coinciding with Batman’s yellow oval costume switch). Batman’s Black Casebook (as gleaned from Batman #678) tells us that, by “5 years into the mission,” the majority of Golden Age tales have already taken place. DC Y5 is basically more of my BY7 (roughly 1964 to 1967).

DC YEAR SIX: More Batman and Robin stories referenced from the Silver Age into the very beginning of the Bronze Age. Pretty much all of my BY8 fits here, comprising of references from 1968 through 1972.

DC YEAR SEVEN: This is the “Penthouse” year. Bronze Age stories galore. Dick goes to college with a very early enrollment. The Saga of Ra’s al Ghul occurs. Damian is conceived.[2] This is my BY9, comprising references from 1973 to 1981.

DC YEAR EIGHT: Dick turns 18-years-old and becomes Nightwing. Nightwing Vol. 2 #132-137 (“321 Days”) implies that Dick turns 18 this year. Jason becomes Robin at age 13 (going on 14). The Crisis on Infinite Earths occurs. Teen Titans Vol. 3 #42 tells us that Kid Devil is 12-years-old during Crisis and 17-years-old in during “One Year Later,” which jibes. This is my BY10, comprising references from 1982 to 1986.[3]

DC YEAR NINE: Barbara is paralyzed by Joker in Killing Joke. Jason is killed by Joker in Death in the Family. Tim becomes Robin at age 13. This is my early BY12. (Timelines in Batman Secret Files and Origins, Villains Secret Files and Origins, Nightwing Secret Files and Origins, and Guide to the DCU 2000 all list Tim debuting as Robin in DC Y9.)

DC YEAR TEN: Zero Hour, Knightfall, and “The Death and Return of Superman” occur immediately afterward followed by Cataclysm and Road to No Man’s Land. My BY12 through early BY16 are all highly compressed into this one single year. Note that, in DCU Legacies, writer Len Wein implies that Superman’s death occurs roughly seventeen or eighteen years after Wonder Woman’s debut! So, as you can see, not everyone at DC is hellbent on über compression. Of course, it only muddles things further to have staff on completely different pages.

DC YEAR ELEVEN: No Man’s Land takes place this year. (In LOTDK #125, Gordon even says Batman has been around for ten years.) The rest of my BY16 synchs up with this year pretty well.

DC YEAR TWELVE: Our Worlds At War followed immediately by Bruce Wayne Murderer and Bruce Wayne Fugitive and then Hush, JLA: Obsidian Age, Superman/Batman: Public Enemies, Death and the Maidens, “War Games,” The OMAC Project, and Under the Hood, and Infinite Crisis. 52 begins. DC Y12 is my BY17, BY18, BY19, and BY20 all squashed into one single year. Judd Winick’s Batman Annual #26 implies that at least three-and-a-half years pass between Jason’s death and “Hush,” which jibes. Jason also turns 18-years-old in Detective Comics #790.

DC YEAR THIRTEEN: 52 concludes. “One Year Later” occurs. Countdown occurs. Grant Morrison’s run begins with Batman and Son, followed by Ressurrection of Ra’s al Ghul, Trinity, Batman RIP, and Final Crisis. DC Y13 comprises all of BY21 and the first third of my BY22. Jezebel Jet mentions Bruce is “over thirty-years-old” (i.e. guesses he is “in his thirties”). It has been mentioned in a note above, but bears a reminder, that Damian debuts in Batman and Son at age ten. This means, like DC does with the short New 52 timeline, Damian’s aging process is artificially sped-up. He would only have been in existence for about five or six years at this point, and yet he’s ten-years-old.

DC YEAR FOURTEEN: Battle for the Cowl starts this year. This is the rest of my BY22 leading up to Batman and Robin and the start of Red Robin. In Red Robin #25, Tim is still seventeen-years-old but about to turn eighteen.

DC YEAR FIFTEEN: Batman and Robin and Red Robin continue. The Return of Bruce Wayne and Batman Incorporated occur. Flashpoint happens at the end of this year. Paul Dini’s “House of Hush,” which also occurs this year, heavily implies that Bruce is nearing 35-years-old. This is my BY23.

___________________

So there you have it. This timeline effectively matches up with everything that DC published in the Modern Age and seems to be the historical foundation upon which Modern Age Batman stories were told. It’s interesting to compare this compressed 15 year history with the albeit still highly-compressed, dense, and detailed twenty-three year chronology I’ve built. Don’t get me wrong, I like DC’s 15 year chronology because of its simplicity and functionality, but it really does relegate everything pre-Zero Hour to altered reference material. And, if you look at how top heavy things are toward the backend, it even seems like it also regards Infinite Crisis in a similar manner, essentially treating it as a hard reboot that wipes out everything prior to create a new timeline loosely based upon seventy years of stories that took place before it. (To my knowledge, no one at DC has officially acknowledged Infinite Crisis as a hard reboot the way they have with Zero Hour, but it certainly looks that way when you examine their 15 year timeline with more scrutiny.)[4][5][6]

___________________

________________________________________________________________________

HOW TO USE THE BATMAN CHRONOLOGY PROJECT

One final note about how to best use my chronology as a reading guide. It’s probably much more enjoyable NOT to break up story arcs and read them exactly as my timeline lists things. Rather, it is probably more enjoyable to read arcs as they were published or collected as trade paperbacks (i.e. as complete stories). If you are reading everything for the first time, I’d use my chronology as a basic framework from which to crib. For instance, there’s no better place to begin in the Modern Age than with Frank Miller’s “Year One.” Maybe “Shaman” can follow afterward. For those that are already quite familiar with the texts and have read most of the narrative already, it might be an interesting exercise to then go back and read things in the exact order from my chronology. But as a first go, I wouldn’t recommend trying to do it. I’d be lying if I said it wasn’t an endeavor to read superhero comics in “correct” chronological order, but, even so, it can be a really fun endeavor, should you choose to engage.[7][8]

_______________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

INTRO TO THE MODERN AGE PART 1 <<<< | >>> EARLY YEARS >>>

- [1]COLLIN COLSHER: It is possible Silver St. Cloud debuts here in DC Y4. Kevin Smith’s storylines in 2010-2011 (from Widening Gyre) tell us that Bruce has known Silver for roughly ten years, thus giving us a reference for the placement of her debut. Even though Widening Gyre is non-canon, at the very least, it shows us the mindset of DC publishers towards the end of the Modern Age. If we choose to ignore Smith’s storyline references because they are non-canon, then we can move Silver’s debut to DC Y7.↩

- [2]AIDAN K: In the DC timeline, there must be the assumption of accelerated aging on Damian’s part, as he is conceived during DC Y7 and is ten-years-old during DC Y13.↩

- [3]ZILCH: A neat point of reference in regard to DC’s version of history is the DC Universe: Legacies series. While problematic in some areas, it gives a good range to the age of the Modern Age DCU in Paul Lincoln’s daughter, Diana, who was born at the start of the Modern Age. In the issue that details Crisis on Infinite Earths she is some where between pre-teen and teen, so at Crisis the modern heroes (Supes, Bats, etc…) have been around for 8-12 years. I would call it 10-13, but I want to give as much space as possible for the teen heroes’ ages. Therefore, DC Y10 seems appropriate for the Crisis on Infinite Earths.

COLLIN COLSHER: DCU: Legacies does imply that the original Crisis occurs in Year Ten, but it still seems to work better for everything else if it’s in DC Y8. However, if one does push it later, it would unfortunately squeeze back Jason’s Death, Babs’ paralysis, and some other stuff into an uncomfortably compressed DC Y10. Up to the reader, but despite the implication in DCU: Legacies, DC still meant for the original Crisis to go in DC Y8.↩

- [4]VALHERU: That DC-version timeline really looks funky, doesn’t it? The Silver and Bronze Ages are basically Y5-8, the Dark Age (or whatever you want to call the post-Crisis/pre-Modern Age) [COLLIN COLSHER: I called it the “Early Period”!] is Y9-11, and 2001 through 2011 is roughly Y12-14. So basically Batman’s first fifty years of publication are six years (excluding Miller and Loeb’s artificial Y1 and Y2), and the last 25 publication years are six more (and if the years of NML and 52 were compressed, the slack would likely go to the Modern Age, not the Silver/Bronze).

See, that’s why I support a graduated timeline: We really can’t be treating the heavily-retconned pre-Modern Years as the same kind of temporal years that pass in the Modern Age, nor can we treat Gotham’s chronology equal to the wider-DCU’s. Loeb’s Y2-4 of Long Halloween and Dark Victory simply don’t exist in the rest of the DCU (it’s even questionable whether Dark Victory exists much at all); the year of NML didn’t seem to pass in the rest of the DCU, and vice-versa, 52‘s year without Batman is more like a week without him in Gotham. When Batman says he plays by different rules than other heroes, he’s not just talking methods: He’s operating on a whole ‘nother temporal plane.

COLLIN COLSHER: Yes, I am quite annoyed that so much slack went to the Golden, Silver, and Bronze Ages, instead of the Modern Age, but if we go by Tim Drake’s four years of aging, then the slack goes where it goes… which leads us to the fact that the DCU does indeed abide by an alternate scientific system of time (or one that lacks science). Trying to apply time to something that so clearly eschews the idea of time is, as I’ve always said, a futile effort. The chronological order of my project is, however, correct even if the applied times and dates are wacky. Regarding the application of specific times and dates to a structured order, there are a myriad of possibilities (including a graduated timeline) that can be applied to the organized events of Batman’s life, and this is a game that can be played an infinite number of times. A whole ‘nother temporal plane indeed… Sometimes it’s best not to think about it (although it’s a little too late for us)!

IAN @ TRADE READING ORDER: The DC version of the timeline is definitely very compressed. However, it kind of makes sense with so much having gone on in terms of issues in the Silver Age/Bronze Age, whereas the Modern Age has all been about storytelling events—meaning things are actually changed after the issues, versus just containing a lot of pages. So, it feels a lot more weird to have that ten to twenty years compressed versus the 1960s-1980s twenty year block. Nice analysis!↩

- [5]AIDAN K: Here’s another alternative. Looking at a couple of lines in Morrison’s “Batman RIP,” I came up with ~18 years in the Bat-suit (at the time of the reboot). Funny that we get a third answer. Eighteen to nineteen years as Batman is a fair compromise down from your twenty-three years (or up from DC’s fifteen years). Here’s my reasoning: First, we have from the “Black Casebook” (i.e. Batman #678) that “five years into the mission” is still the Silver Age, though it appears to be the tail end. Add eleven years for Damian’s age (assuming no accelerated growth in the Modern Age), a year for his gestation/time for Bruce and Talia to fall in love in a whirlwind three months, and a buffer year between the Silver Age and Saga of the Demon [where Dick leaves, etc.] and we get roughly eighteen years of Batman.

COLLIN COLSHER: As I always say, there are an infinite number of possibilities. I am open to all of them. However, my challenge to Aidan’s timeline is that the “five years into the mission” line from Batman #678 actually tells us that much of the GOLDEN AGE stuff—NOT Silver Age—occurs in the first five years of Batman’s career. Nor does it definitively mean that the Golden Age stuff immediately ends after five years. Thus, my reasoning for adding a four or five extra years is to accommodate the vast number of stories being squeezed into continuity, which includes the Silver Age tales. This is also the reason for my version of events lasting twenty-three years instead of merely 18 (or 15).↩

- [6]FRANK FERNANDEZ: Yet another viable option, and one that would add a couple extra years to the overall timeline, is the application of the “four years for every one in-story year” rule (aka Marvel’s “4-1 rule”), at least to the first twelve or so years of the timeline. In doing so, items—notably character collegiate duration and the like—tend to fall into place quite well. Of course, taking this route paints a different timeline than the one presented by the Batman Chronology Project (pushing the original Crisis a couple years back in comparison), but this version ultimately winds up functioning just as effectively.↩

- [7]COLLIN COLSHER: Here is an “essential” comprehensive list of Modern Age Batman trade paperbacks in chronological order. Bear in mind, these aren’t necessarily the best stories, but the most important available in collected trade format. Of course, there are great single issues that are collected in random “best of” trades as well, but those are harder to insert into a list.

—Batman: Year One by Miller/Mazzucchelli

—Batman & The Monster Men by Wagner

—Batman & The Mad Monk by Wagner

—Prey by Moench/Gulacy

—The Man Who Laughs

—Shaman by O’Neil/Hannigan

—The Long Halloween by Loeb/Sale

—Dark Victory by Loeb/Sale

—Robin: Year One by Dixon/Beatty/Pulido

—JLA: Year One by Waid/Augustyn/Kitson/Bair/Garrahy

—Batgirl: Year One by Beatty/Dixon/Martin

—Dark Detective by Englehart/Rogers (aka Strange Apparitions)

—The Collected Saga of Ra’s al Ghul by O’Neil/Adams

—Nightwing: Year One by Beatty/Dixon/McDaniel

—The Crisis on Infinite Earths

—Justice League International Vol. 1 by Giffen/MacGuire

—Ten Nights of the Beast

—Arkham Asylum by Morrison

—Justice League International Vol. 2

—Cosmic Odyssey by Starlin/Mignola

—Killing Joke by Moore/Bolland

—A Death in the Family by Starlin/Aparo

—Birth of the Demon

—Vengeance of Bane

—Knightfall/Knight’s End

—JLA: New World Order by Morrison

—JLA: American Dreams by Morrison

—JLA: Earth-2 by Morrison/Quitely

— “Cataclysm”

— “No Man’s Land” (the government declares Gotham a wasteland, cut-off from the rest of society)

— “Bruce Wayne: Murderer/Fugitive” (Bruce is framed for murder)

— “Hush” (introduction of Hush)

— “War Games” (crime war involving Black Mask, Stephanie Brown as Robin)

—Identity Crisis

—The OMAC Project

— “Under the Hood” (Jason Todd returns)

—Infinite Crisis

— “Black Case Book” (beginning of Grant Morrison run)

— “Batman and Son” (introduction of Damian aka Bruce’s son with Talia)

— “Batman RIP” (the final Bruce Wayne story-arc before Final Crisis where he “dies”)

—Final Crisis

—Batman & Robin: Batman Reborn

—The Return of Bruce Wayne

—Batman Incorporated Vol. 1

—Batman Incorporated Vol. 2For a full list of trade paperbacks in chronological order, please check out a collected edition timeline by the amazing AzureNight64.↩

- [8]COLLIN COLSHER: As mentioned before, everything that DC publishes is meant to be “in-continuity” in some regard. Some of the books take place on different Earths (Batman Beyond Animated Universe, The Brave and The Bold Animated Universe, etc…), placing them “out-of-continuity” i.e. not happening on the main DCU Earth. Some books are hard to tell if they are in-continuity or out-of-continuity. For example, Kevin Smith’s Batman run, Batman: Odyssey, and a few JLA inter-company crossovers are next to impossible to fit into any chronology no matter how much the writers of these tales insist otherwise.↩