…continued from Relaunched, Rebooted, and Bewildered…

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

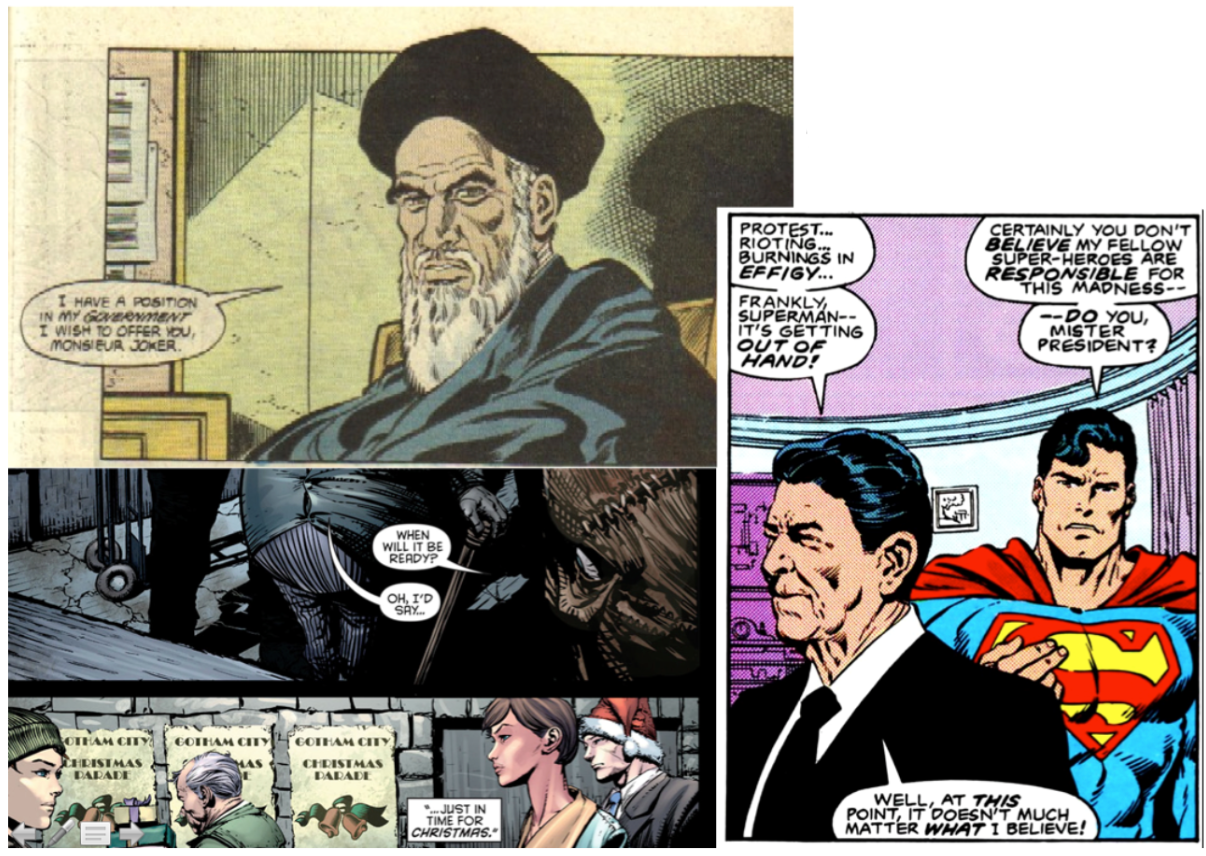

BUILDING TIMELINES FOR DUMMIES

In his 2023 book Reboot Culture, William Proctor is not only kind enough to reference the Batman Chronology Project by name, but he also wonderfully describes the work being done on this site (and others like it) using the term indexical labor. Proctor defines indexical labor as any “fannish project, undertaken by super-readers, of taxonomizing, scrutinizing, policing, and cataloguing an imaginary world’s narrative architecture, highlighting continuity snarls as they go.” This aptly represents the nature of the Batman Chronology Project, although my hope is that there’s less individual policing and more collaborative interpretation when it comes to the construction of said narrative architecture. Nevertheless, in order to scaffold something that won’t topple, there must be rules. Following a 2017 presentation in Portland, Oregon entitled “The Complete and Unabridged History of the Marvel Universe,” author Douglas Wolk commented that his method of schematizing and “way of reading” superhero comics is “what Steve Lieber smartly called a ‘Bible-as-literature approach’—tending to treat everything as valid evidence to be assessed unless it’s specifically not. You can’t declare an issue non-canonical because ‘Dr. Strange wouldn’t do that’; the only valid reason for excluding a story is ‘Dr. Strange didn’t do that!” Lieber’s Bible-as-literature approach, which Wolk has so perfectly applied to the Marvel Universe, is something that I’ve also applied to the DCU when making Batman timelines.

In his 2023 book Reboot Culture, William Proctor is not only kind enough to reference the Batman Chronology Project by name, but he also wonderfully describes the work being done on this site (and others like it) using the term indexical labor. Proctor defines indexical labor as any “fannish project, undertaken by super-readers, of taxonomizing, scrutinizing, policing, and cataloguing an imaginary world’s narrative architecture, highlighting continuity snarls as they go.” This aptly represents the nature of the Batman Chronology Project, although my hope is that there’s less individual policing and more collaborative interpretation when it comes to the construction of said narrative architecture. Nevertheless, in order to scaffold something that won’t topple, there must be rules. Following a 2017 presentation in Portland, Oregon entitled “The Complete and Unabridged History of the Marvel Universe,” author Douglas Wolk commented that his method of schematizing and “way of reading” superhero comics is “what Steve Lieber smartly called a ‘Bible-as-literature approach’—tending to treat everything as valid evidence to be assessed unless it’s specifically not. You can’t declare an issue non-canonical because ‘Dr. Strange wouldn’t do that’; the only valid reason for excluding a story is ‘Dr. Strange didn’t do that!” Lieber’s Bible-as-literature approach, which Wolk has so perfectly applied to the Marvel Universe, is something that I’ve also applied to the DCU when making Batman timelines.

Aside from the Lieber method, deciphering superhero comic book continuity requires the application of historical criticism. As scholar Jeffrey Hayes says in his article “Continuity and Deep Fictional Universes” (2021), one must hold a critical eye toward chronological publishing considerations, serialization, content, setting, context, and cultural and topical specificity. My timeline-building catechism factors in these items—plus everything we’ve previously discussed regarding fictional canon and line-wide REBOOTS. But as stated earlier, reboots never really start over completely from scratch. Old stories get folded into “new continuity” in interesting ways. Because the “superhero story” generally exists in the form of serialized multiple-authored sequential art, we see types of storytelling in superhero comics that are unique only to superhero comics. Thus, there many specific kinds of “funny games” that creators play to tell superhero stories (or play while telling them). This section of my site is all about these funny games that creators play and that fans (myself included) interpret. The collaborative perception of both authors and readers is what makes superhero comics superhero comics. It is through this exchange that a superhero universe gains cohesion and coherence.

Be aware that, with most examples that show my personal interpretive process as a reader, there can often be various alternate interpretations to open-texted material. Again, this is the Barthesian idea that fandom dictates canon. Applying the Barthes-influenced narrative theory of David Herman, Proctor describes mainstream comics as “especially polychronic in that they exploit a fuzzy temporality—a strategically inexact mode of narration that makes sequential (re)organization tasking.” As such, make sure to chant the following shibboleth as you drudge your way through the labyrinth that is superhero continuity: There is no one true correct answer. Even if you come to regard the voice of this website as an all-empowered arbiter, don’t forget, the goal here is simply to achieve the best possible reading order, one that makes the most sense narratively and chronologically. Let’s now look at a few examples to show how the collaborative perceptive nature of continuity-building works (for both author and reader).

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

FLASHBACKS, REFERENCES, EASTER EGGS, BROAD STROKES, & RETCONS

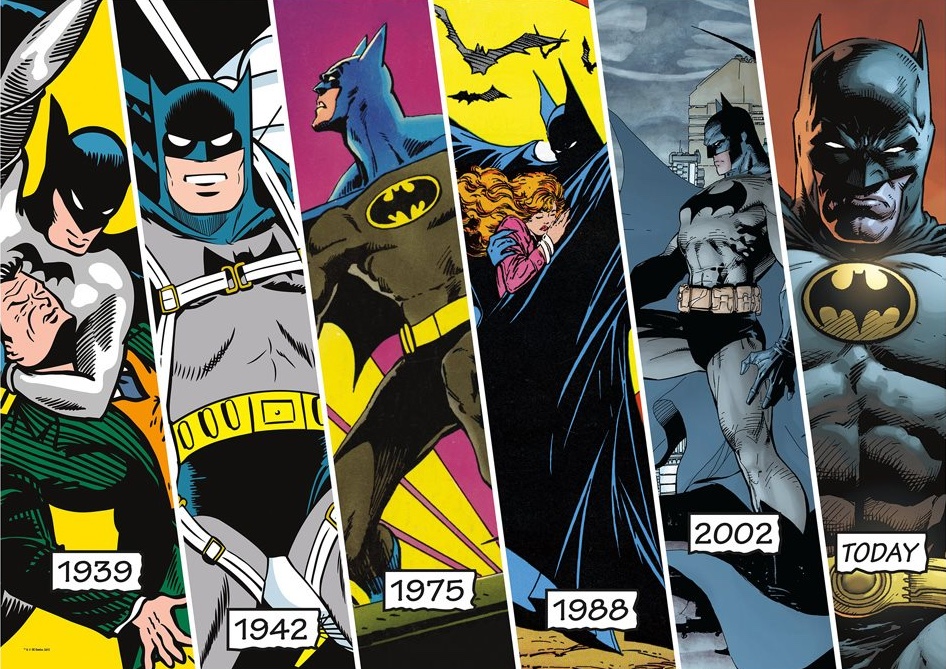

A novel flashback from Batman Eternal #11 by Tim Seeley, Scott Snyder, James Tynion IV, Ray Fawkes, John Layman, Ian Bertram, & Dave Stewart (2014)

My timelines appear primarily as lists containing chronologically ordered storylines (coming from the ongoing contemporary narrative of comic books). However, my timelines also contain a lot of flashbacks and references too. A flashback is whenever an ongoing contemporary narrative interjects a scene of a past event. Similarly, a reference is whenever a past event is mentioned or nodded to during ongoing contemporary narrative. Flashbacks and references can be unique, meaning that they show or mention something that hasn’t been shown or mentioned before. These types of flashbacks and references must be inserted into history at a locus that makes sense. Flashbacks and references can also show or mention things we’ve already seen in relation to the ongoing contemporary narrative. These flashbacks and references must be attached to the item being re-shown or alluded to. Sometimes specific times are given (i.e. “x years ago”); sometimes they are not. (It’s better for authors not to dwell in specificity since it only increases the risk of error or contradiction.)

Flash-forwards and future stories (i.e. any in-story narratives that show the future of a timeline) exist too. When it comes to how readers and writers view the future in multi-authored serialized comic book universes, things can be tricky, especially since readers and writers tend to place more weight on the continuity of the present day versus stories that deal with the future. As such, it becomes easier (and more common) to invalidate the wishy-washy future than other continuity. This shouldn’t necessarily be the case, but it unfortunately it is. For more details on this phenomenon, check out my blog article “Physics of the Future.”

Easter Eggs are a fun type of reference example. The Batcave trophy room is filled with them. Basically, the Batcave trophies have long existed as a means for artists to have fun and draw in whatever they please. But when this happens—let’s say, for instance, someone draws a gigantic mushroom in there—it means that Batman went on some unspecified mission and netted a giant mushroom as a prize. This becomes a part of his history that we can only imagine in our own minds!

A broad strokes flashback to prior continuity from Superman/Batman #31 by Mark Verheiden & Matthew Clark (2006)

In comics, flashbacks and references can also refer to previous continuity. These flashbacks and references sometimes show exact images or mention exact things that happened in prior canon, but they sometimes can also be written-in using broad strokes i.e. when things don’t match perfectly to prior canon but still capture the essence of the scene. Sometimes, this includes out-and-out retcons. Here’s a little thought exercise to help us better understand: Let’s take all of the adventures from 1964 through 1986 that Batman goes through. After reboot in 1986, that stuff all gets totally erased, but casually referenced or flashed-back to by various authors that want to draw upon Batman’s rich history. However, those references and flashbacks cannot happen exactly as they did since they fit into a new updated, modern continuity. Thus, they become retroactive reference material, a mere skeletal framework of what once was that resembles the past but has now been altered to fit the present. Sometimes things look very similar to what was once before, corresponding perfectly in chronological order and visual appearance. But sometimes things get redefined to such an extent that they will bear no resemblance to their prior understandings. Ironically, we (the reader) do most of this redefining in our own minds with the stimulus being the authorial nod within the current narrative. Another way of looking at this concept is that a new continuity is inspired by or based on prior continuity. The New 52 is inspired by the Modern, Silver, and Golden Ages whereas the Modern Age is inspired by the Silver and Golden Ages (and so on and so forth). Since new continuity is based on old continuity, it’s important for writers to try to adhere to the original order of previous continuities when drawing upon history for their contemporary narratives. The old continuities are the only thing that provide a shared solid foundation (i.e. a generally agreed-upon historical consensus) for writers to draw upon.[1][2]

How do we know a retcon when we see one? And, when we spot one, how should it be addressed? Sometimes retcons simply change continuity while ignoring the past, but retcons can also function intradiegetically (by having an in-story event that alters the past to modify continuity). No matter what, though, most timelines are generally molded in the image of previous timelines. The goal in building a new timeline should be to mirror the old ones as much as possible. Of course, that can’t always be done. Also, newer (more recent) publications tend to trump older releases. The opposite almost never happens, but there are always exceptions. An example of a newer story retconning a piece of an older story would be The Man Who Laughs (2005) retconning the end of Miller’s “Year One” (1987). Exceptions to this rule would apply to retcons from later publications deemed non-canonical or quasi-canonical. (Novelizations, supplemental material, and similar fringe releases typically fall under the quasi-canonical category.) Here’s the big thing to remember: Not everything contradictory from a later (newer) story is meant to be a retcon. Some writers simply make mistakes! It’s up to the reader to determine what is a retcon versus what is a continuity error. In this way, we have a loophole to all of our aforementioned edicts. It’s a difficult process determining what is or isn’t a retcon, and, as said before, it certainly isn’t an exact science with hard rules. Thus, we get caveats that say what needs to be ignored. Honestly, continuity is a mug’s game. The idea is simply to come up with the best (most sensible) reading order while simultaneously providing detailed explanations (i.e. proof or evidence) behind the rationale.[3]

Original ending to Batman: Year One by Frank Miller & David Mazzucchelli (1987). Newcomer Joker, having not yet debuted, has publicly threatened the reservoir, but Captain Gordon isn’t worried.

Batman: The Man Who Laughs by Ed Brubaker & Doug Mahnke (2005). In a retcon of Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One, Joker, who has already debuted, ambushes the reservoir without warning, much to the shock of Captain Gordon, who is very worried.

While almost anything could be in-continuity, canonization requires proof or evidence in the form of a reference or a flashback—big or small, obscure or obvious, but proof nonetheless. This is the number one rule when building timelines. For example, we know Kite Man exists in both the Silver/Bronze Age and Modern Age. Could every single one of his Silver/Bronze Age appearances be canon? Theoretically, they could be. But take each one of those appearances one by one, analyze each issue, and ask yourself if it’s definitively canon. That’s very hard to do, maybe impossible in most cases. Following this same thru-line, we know Kite Man exists, we know he is Batman’s foe, and we know his general schtick. From that, all we really know is that his first appearance is definitively canon. If there’s something essential to his character development, something absolutely crucial (again that’s extremely difficult to determine), then sure, that could be canon. Again, it’s not as definitive as before. All we know is that a reference or flashback functions as proof, and without proof, the rest is conjecture—and even if one can reasonably argue in favor of it, it still remains conjecture.[4]

Can narrative be canonized piecemeal from within a single comic? In other words, can parts of a comic be canon while other parts of the same canon are not? My methodology doesn’t involve picking and choosing pieces of individual comics. Typically, a full issue is either canon or it isn’t. The only time pieces of a single comic get added are via reference (or the occasional dreaded out-and-out retcon). It’s up to the reader to separate the wheat from the chaff while making things fit into the greater puzzle—either by fanwank or caveat citing a retcon/irreconcilable difference. (A fanwank is a reader-applied teleological explanation for an ostensible continuity error.) This kind of finalism is certainly not an exact science—and I’m sure I break my own rules every now and again. But I really try not to.

How do we know if something is definitively non-canon? Again, aside from Elseworlds tales, we cannot know with 100% certainty. While building my timelines, I’m simply searching for meaning and intent in order to provide sense. Therefore, I’m hesitant to remove items entirely or to flippantly label things non-canon, even when they have errors. Doing so would set a dangerous precedent that could conceivably lead to removing just about everything! If you counted-out things based upon continuity errors, there’d be very little left. I’d rather fight to keep things on the timeline, when possible. Writers generally have clear intention of where they want their comics to occur, even when they fuck up continuity. If something is truly unplaceable (going beyond having a small number of errors) and there’s really no clear narrative intent that can be discerned, then we can and should consider disavowal.

Retcons about the Wayne murders: Zero Hour (Batman #0 by Doug Moench & Mike Manley, 1994) vs Infinite Crisis (Infinite Crisis #7 by Geoff Johns et al, 2006).

Sometimes soft reboots cause retcons as well. For instance, 1994’s Zero Hour retconned things so that Joe Chill was no longer the Wayne killer. (This was but one of several Zero Hour changes, but we’ll use this as our example.) All of a sudden, the identity of the Wayne killer was unknown even though it had been known for many years. Eventually, 2006’s Infinite Crisis undid Zero Hour‘s retcons, returning things to as they were. However, as a result, there are a lot of instances during the 1994 to 2006 period where we just have to ignore any references to the Wayne murder case being unsolved. Interestingly, in 2020-2021, DC utilized a very novel in-story way to view aborted retcons and returns to status quo in the form of collective memory blockage. The New 52 and start of the Rebirth Era were decidedly different than previous timelines, missing large chunks of information and entirely omitting characters—like the JSA, Legion, some Teen Titans incarnations, Young Justice, Flash Family members, and more. All of the above were non-existent and non-canon starting in 2011 with the outset of the New 52. Then, these characters and teams began sporadically re-appearing around a decade later. DC’s novel intradiegetic explanation was that Dr. Manhattan erased (i.e. removed, blocked, or stole) the histories and memories of the above characters and teams when he created the New 52. As such, DC gave a reason for why the New 52 is missing so much and why no one seemed to recall or be aware of what was missing. When status quo returned, the wishy-washy continuity alteration seemed more like authorial story choice as opposed to an aborted retcon. With Zero Hour and Infinite Crisis, creators made retcons and then later undid those retcons. New 52 and Rebirth might be the exact same kind of thing, but the big difference is that the creators built an explanation for their retcons and aborted retcons into the narrative.

Bruce marrying Selina as part of an Earth-2 retcon in DC Super-Stars #17 by Paul Levitz & Joe Staton (1977)

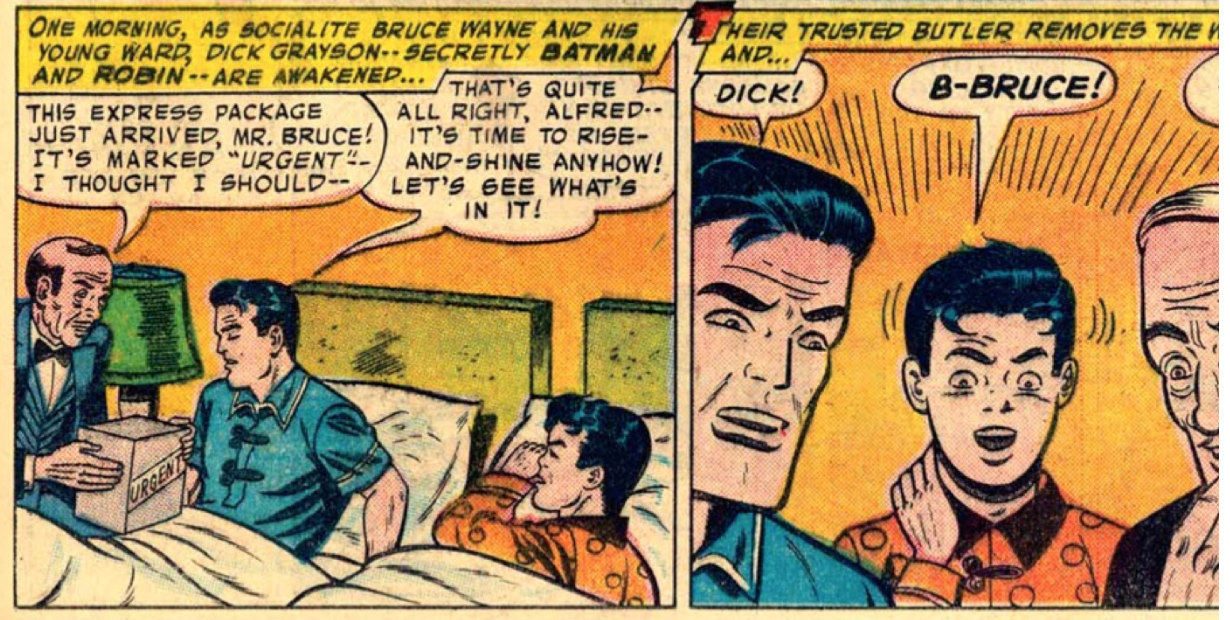

Specific Golden Age (Earth-2) timeline retcons from the 1970s and 1980s cause a lot of alteration. In the 1970s, Bruce and Selina are retconned to have been married with a baby, so a bunch of stories from the 50s and early 60s don’t fit! Batman #117 Part 2 is an example of a story that no longer make sense if Bruce is happily married to Selina. A married Bruce would probably be sharing a room with his wife, not Dick. Come to think of it, why is Bruce sharing a room with his young ward? And why are the beds pushed so close together? Notably, the curious panel from Batman #117 Part 2 (along with a very similar image from Batman #84 Part 3) was unfortunately (and unjustly) used as execrable ammunition by Fredric Wertham during his witch hunt against comics in the 1950s.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

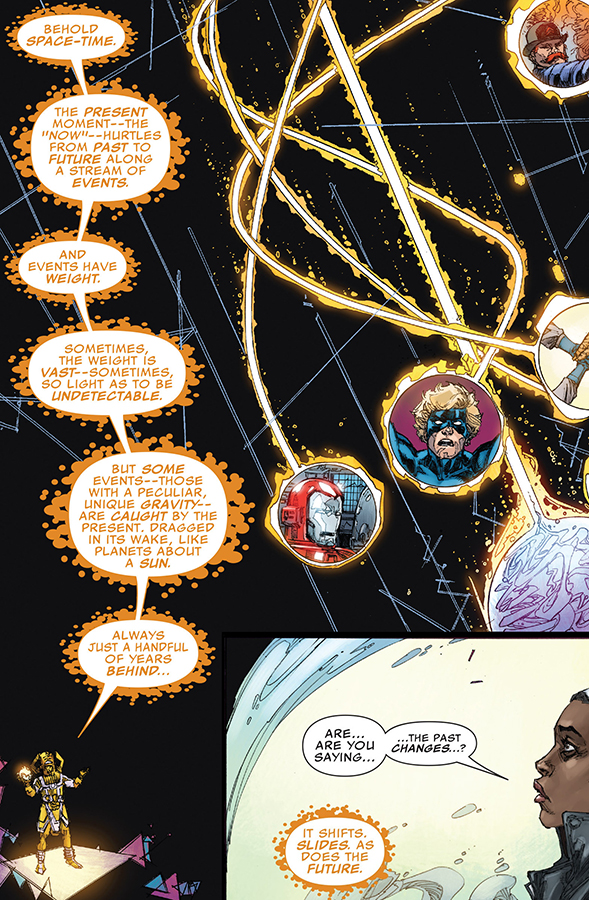

SLIDING-TIME, COMPRESSION, TOPICALITY/SEASONALITY, & MILESTONES

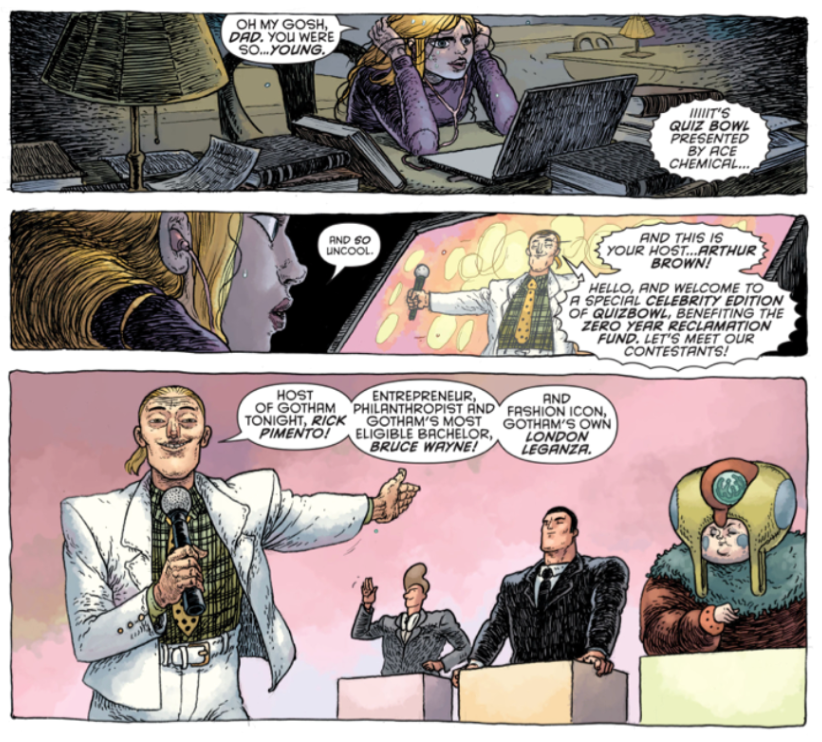

Superman (from Superman #170 by E Nelson Bridwell & Al Plastino, 1964) retconned into Superboy (from Superboy Vol. 2 #27 by Bob Rozakis, Jose Delbo, & Dennis Jensen, 1982) as per Sliding-Time

Sliding-Time (aka Time-Sliding or use of a Sliding Timescale or Floating Timeline) occurs in both the Silver/Bronze Age and Modern Age. Retcons in the late 1970s and early to mid 1980s, as gleaned from hints in the narrative of several titles, caused the start dates for DC characters, including Batman, to be “slid-up.” More than just a hint, this becomes obvious when Superman meeting JFK gets changed to Superboy meeting JFK. Likewise, DC did the same thing starting in 1994 with Zero Hour, and slid things up annually until around 2002.

Interestingly enough, sliding-time is one of the big reasons that one can build DC chronologies with strict(ish) dates and times whereas building Marvel chronologies the same way is nearly impossible. Initially, from 1961 onward, Marvel operated with a timeline that was roughly step-in-step with realtime. However, following the debut of the character Franklin Richards in 1968, Marvel initiated a sliding timescale that, throughout 1970s and into the 1980s, would increasingly distance its timeline from the realtime calendar, squeezing years’ worth of publications into tighter and tighter narrative spaces. As detailed in Chris Tolworthy’s “Fantastic Four as the Great American Novel” thesis, by the late 1980s, Marvel’s sliding timescale had completely erased any semblance of realtime coextensivity. In fact, since around 1989, Marvel has operated (and continue to operate) with a sliding timescale that constantly moves to keep its shared-multiversial start date perpetually around fourteen or fifteen years prior to current ongoing publications. In other words, a contemporary Marvel story arc (and all topical/seasonal references within) is instantly retconned into skeletal reference material as soon as a new arc replaces it. This means Marvel doesn’t really have a set timeline so much as it has a reading order that is constantly anchored to present day. Past (and future) truth can only ever be gleaned from the most recently released publications. Characters don’t really age—they stay young. And it doesn’t appear as if Marvel will alter this chronometric protocol anytime soon. In contrast, DC’s floating timelines have always altered origin-points with exact specificity. While indeed “floating” like Marvel’s, they never constantly floated. Instead, they’d be editorially moved (sometimes officially but sometimes unofficially) every now and again, and not that often.

Time compression alters the length of “No Man’s Land—as originally seen in Batman #573 by Greg Rucka & Sergio Cariello (2000)

Compression (aka timeline-shortening or shortening of timelines) occurs quite often as well. Reboots and retcons are conducive to significant time-compression. For instance, as briefly touched upon above, sliding-time causes massive compression. Say a story arc (like “No Man’s Land” or “Knightfall”) occurs over a specific nearly yearlong in-story period. When things are made more contemporary, large chunks of story time cannot accommodate the shorter more-updated timeline. Thus, we have to imagine a condensed history. Instead of a full year, “No Man’s Land” only lasted a few months. Or Batman recovers much faster after Bane breaks his back in “Knightfall” etc. Furthermore, even though new continuity is generally based upon old continuity, the new canon is usually compressed in order to fit new material and accommodate the narrative flow of the new timeline. For example, DC’s Modern Age Year Six is loosely based upon nine years of Golden/Silver Age material (1955-1964). That’s a lot of story being compressed down to a single year. Because of this, you usually have to ignore the seasonality or topicality of the original story in order to make it fit into contemporary canon. Marvel Comics has long held the concept of four years’ worth of publications equaling one year of in-story narrative (retroactively, of course). DC has never officially used this rule, but it’s apparent that it has been enacted at certain points.[5]

Another significant aspect of compression can be seen in DC’s 2011’s Flashpoint reboot, in which the entire line was re-launched. Editors were fearful of the reaction that fans would have to a completely rebooted Batman with no past to speak of, so while Batman still had to fit on the six-year-long timeline, his entire history, including multiple Robins, still existed! This led to speculation on the internet as to how this could be possible. My site maps this out pretty damn well. But basically, as of right now, Batman’s entire history has been squeezed into a seven year timeline. Robins go from side-kicking for years to just having been “interns” for a year or less in order to make things work. The key events and stories are still there, but they are skeleton versions of what they once were. And some of them are merely perfunctory references, dropped in conversation between two B-list characters.

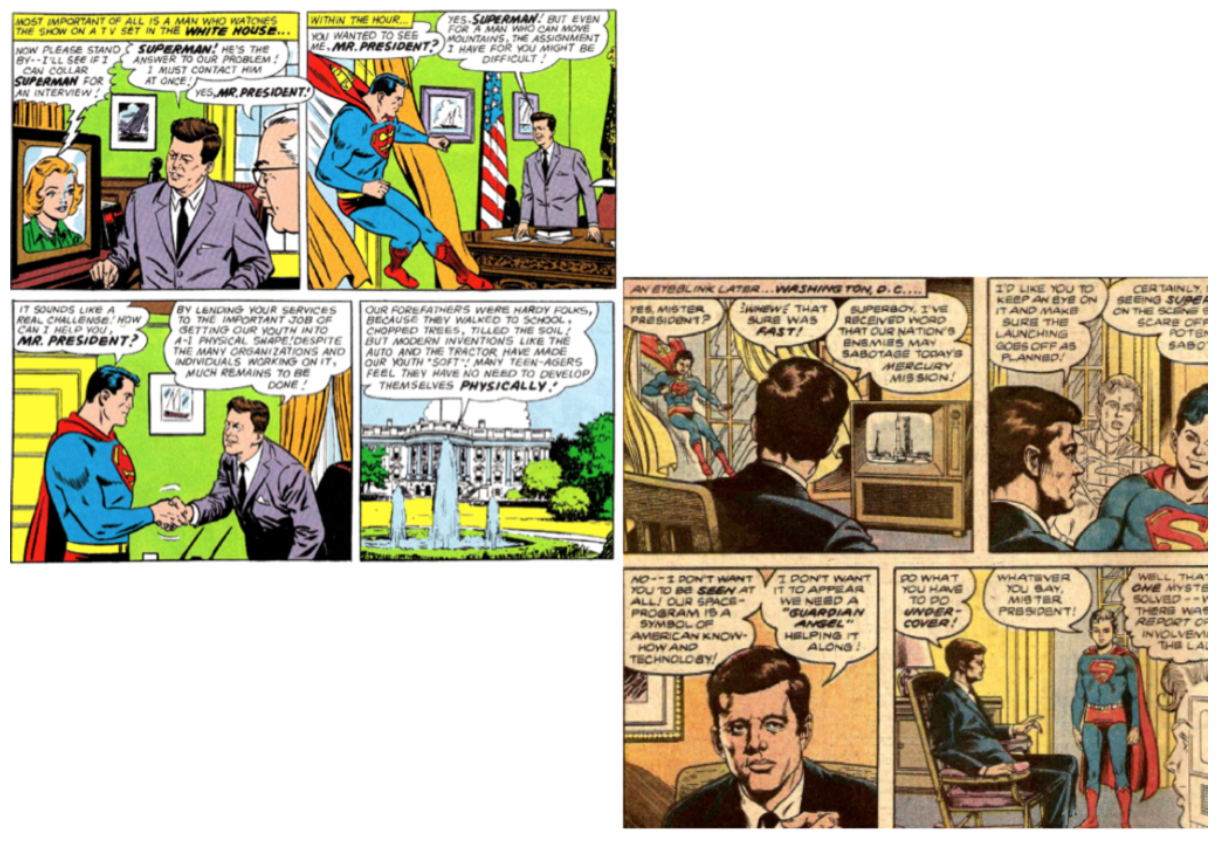

Topical/seasonal specificity that must be ignored in “Legends” by John Ostrander, Len Wein, John Byrne, & Karl Kesel (1986), “Death in the Family” by Jim Starlin & Jim Aparo (1988), & Batman: The Dark Knight Vol. 2 #16 by Gregg Hurwitz & Ethan Van Sciver (2013)

Topical/seasonal shifts are also common. We’ve already said how topical or seasonal references sometimes have to be ignored with a sliding timescale, but they also must get ignored for a few other reasons. For example, many books in the mid to late 80s were prominently about the Cold War and featured Reagan, Gorbachev, the Ayatollah, and Soviet army stuff galore. Of course, decades later, DC tells its readers that Batman hasn’t been around since the 80s, but instead only debuted in the 90s (or 2000s, or 2010s, etc), which means those Soviet stories don’t make a lick of sense. Christmas stories are rough too. It’ll often seem as though there are multiple Christmases in a single year when writers and editors don’t communicate with one another. Since writers are playing with so many others in the sandbox, things must gel and jibe with the rest of the line. The second someone writes something, it has to get slotted in with a thousand other stories, so in terms of continuity, specific topicality becomes secondary to other more important factors. For example, even if a comic book says that it’s summertime (or specifically July, or the “coldest night of the year,” etc), we can’t necessarily take these statements as fact. Just like a Soviet story wouldn’t make sense in the year 2020, the specificity of July might not make sense for a story that is adjacent to an arc that just took place on New Year’s Eve. In fact, just as a writer in the 1980s might have included Soviet references, a writer that has a publishing deadline in July might set his story in July. Again, we can’t take topical specificity as gospel. In summary, if the setting causes the tale to not connect properly to other nearby stories, then the setting of said tale must be ignored. Because of this, it would behoove those writing for a shared universe to avoid topical specificity when it doesn’t have a direct bearing upon narrative.

Milestones, unlike topicality or seasonality, are incredibly important and not to be ignored. As the brilliant Chris J Miller says, “Elections and holidays, school years and sports seasons, birthdays and pregnancies do matter. They can’t always be taken at face value, unfortunately, and sometimes it calls for some clever thinking to accommodate them… but that effort is worthwhile whenever possible to maintain the integrity of the stories. I do, as a broad guideline, grudgingly accept the goal of keeping the characters as young as logically possible (notwithstanding my preference for real-time aging). Likewise, it’s usually reasonable to place ambiguous events at the most recent possible dates. However, I do insist on using real dates, for the sake of clarity and simplicity, rather than the sliding ‘X Years Ago’ format.” The Batman Chronology Project follows the above practice as well.

Even though milestones help us determine exact character ages and passage of time, radical character changes can throw a contradictory wrench into the works. Sometimes, depending on the writer, personalities, sexual preferences, genders, races, or ages change (or don’t change when they should, in the case of the latter). The act of slowing down aging rears its ugly head quite often. For example, most young character ages are screwy, depending on the era. In the Modern Age, Tim Drake was seemingly in high school for way too long. Likewise, Dick Grayson was the same way in the Golden Age. Stuff like this—i.e. the idea of keeping characters perpetually fresh—can lead to some pretty shoddy continuity. Furthermore, characters killed off by one writer can be resurrected by another—either by straight-up retcon or by some retroactive narrative twist. Even stories intended to be non-canon or quasi-canon (like Alan Moore’s The Killing Joke, for example) can be canonized by later writers.

The Killing Joke is fun to talk about because it’s such a seminal title—so crucial and yet so polarizing. It was long hailed as a classic only to later come under scrutiny as being possibly misogynistic and poorly constructed. Even Alan Moore himself has disavowed it (although he’s disavowed all of his work from that era, so take that with a grain of salt). Purportedly, Moore was told this story would be out-of-continuity, which likely affected his plot. In 2015, artist Jesse Hamm did his take on an alternate version (pictured above to the right) of the infamously gratuitous scene where Barbara Gordon is thrown into a fridge and paralyzed by the Joker. Hamm added the comment, “There, I fixed it.” (This is obviously fan art and not canon, but it’s great, so I thought I’d include it.)

You also have the great Brian Bolland redoing the Bat-symbol for the 2008 Absolute Edition of The Killing Joke just because he liked the way it looked better without the yellow oval. But that messes with continuity! Batman’s different costumes are loosely connected to different periods of his crime-fighting career.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

THE OMNIVERSE & ALTERNATE CONTINUITIES

Everything technically exists in some (alternate) continuity, which calls into question the the difference between non-canon and out-of-continuity. There are multiple or maybe even infinite Earths—(the Big Two has called stories happening in these alternate universes “Elseworlds,” “What Ifs,” “Hypertimelines,” or “imaginary tales”)—which means the idea that everything that gets published/produced can take place on its own timeline is not that far-fetched. In this fashion, everything that DC publishes or produces is canon… somewhere in the omniverse. For example, a colleague of mine advocates timeline placement for all sorts of non-comic book Batman ephemera from the 60s, 70s, and 80s—either on a mashed-up collection of timelines or with each type having its own unique alternate universe. There has long been an argument among fans and editors as to how all of the published/produced material should be categorized (and if all of it should be categorized in the first place). Obviously, every item that gets published or produced cannot coexist on one unified timeline. Such a timeline would merely be a list, lacking order and sense. Comic book scholar Brian Hibbs puts it best: “If everything [is canon], then arranging it all in a way that makes sense isn’t just difficult, it’s pointless.” So, as you can plainly see, not everything can be canon on a singular chronology. You have to have Earths A through Z until infinity.[6]

Overall, continuity is a thing that is getting much more attention from the mainstream eye, ironically less so in comics than in Hollywood. This is thanks to the ever inflating bubble of superhero digital media franchises (namely the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the DC Extended Universe, James Gunn’s DCU, and Marvel and DC’s respective TV universes), the lasting impact of numerous horror franchises (including The Walking Dead), and the continuation of never-ending big moneymaking stories like Terminator, Harry Potter, Transformers, Star Wars, Star Trek, James Bond, Godzilla, Planet of the Apes, Rocky, Rambo, Fast and the Furious, Mission Impossible, and more). Sites like Wookiepedia, and various other wiki-style sties now exist to collect and categorize heaps of story/character data in encyclopedic, easily-searchable fashion. For the crème de la crème of chronologies, see Jagm’s Adventure Time chronology. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the video gaming community that is intensely interested in continuity as well.

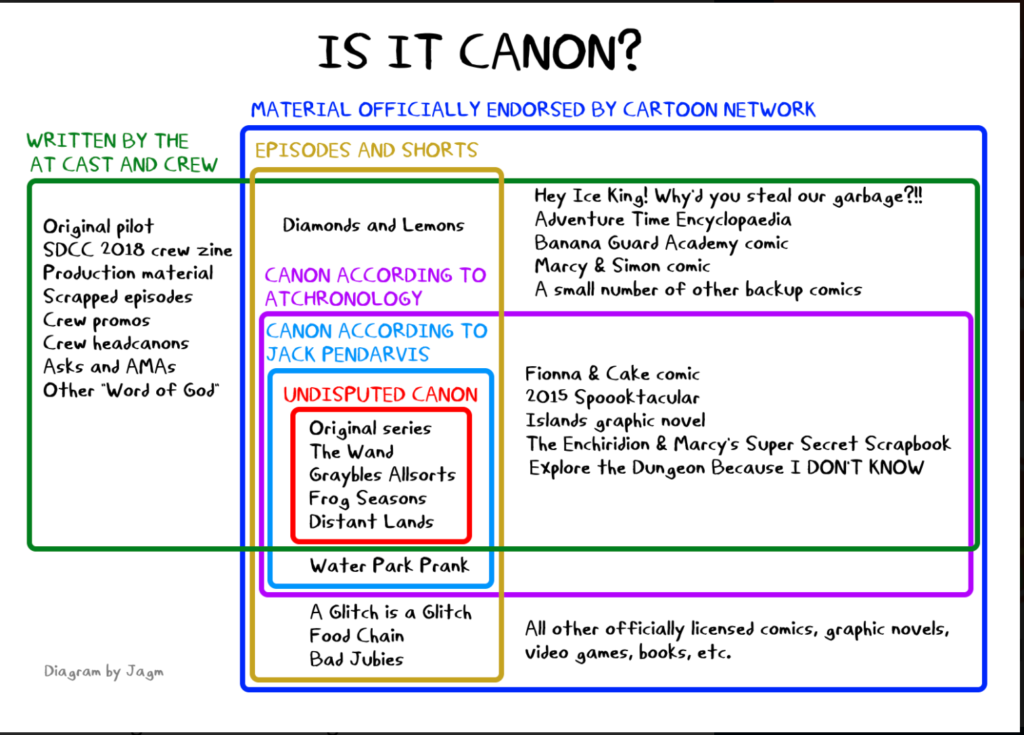

Jagm’s “Euler Diagram”—a scaled Venn diagram detailing the canonicity of Adventure Time comics

Every day, one can stumble upon a plethora of other complicated things involved with canon that I haven’t mentioned. Since 2000, Lucasfilm/Disney has had a single authority in charge of continuity for Star Wars canon. For a time, there were different level-designations of canon within the Star Wars universe—G-canon, T-canon, C-canon, S-canon, N-canon and D-canon. Now Star Wars has both an “official” canon and a “legends” or “extended” canon. Hell, Star Wars has a canonical theme park for crying out loud! The sprawling canon of L Frank Baum’s Oz series, dating back to 1900, is still officially maintained by the Baum Family Trust. Legend of Zelda has three highly particular timelines that branch out from one principal timeline. Star Trek has multiple canons, which have now become intertwined with reboot films. The Dragon Ball, Conan the Barbarian, and Transformers franchises are very similar examples—each with varying levels of “official” canon. Even HP Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos, which dates back to 1917, has several layers of “official” canon.

Even more mind-boggling terms seem to make the concept of fictional canon even more complex—words like fanon, canon immigration, Jonbar hinge, deuterocanon, canon fodder, canon welding, recursive canon, and many more are always popping-up on websites and forums these days. As you can see, there’s always more to say when it comes to matters of chronosophy, canonicity, and continuity. These are topics I enjoy discussing and ones that will hopefully be talked about even more in the future. I’m always glad to be at the vanguard of that discussion, and I am eternally grateful to have had such a positive response from fans/readers both on the internet and at my live speaking engagements.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

PARTING WORDS

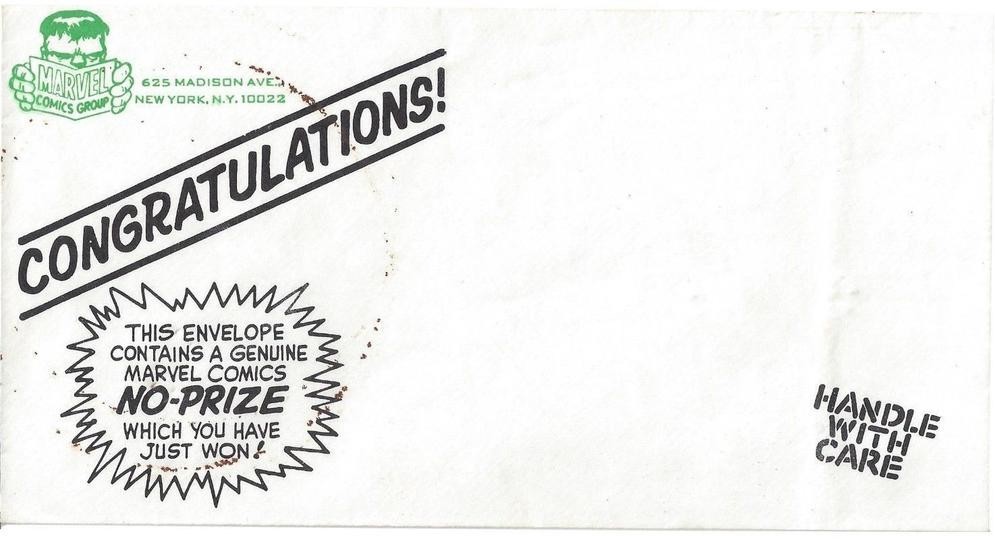

A genuine Marvel Comics No-Prize.

Now that we’ve detailed the methodology of the Batman Chronology Project, we can tackle the big question: “What is the correct chronological order for reading Batman comics?” Quid est veritas? Since continuity truly is in the eye of the beholder, readers can often explain why ostensible continuity errors aren’t really errors at all, putting their own spin on things in order to come up with exegeses. In the 60s and 70s, legendary troll Stan Lee used to mail out “No-Prize” awards to inventive and creative fans that were able to do exactly that. One of my goals is to be the most creative fan there is, the fan that wins the most No-Prizes.

A literal Batman puzzle.

Each section of this website details a very specific order and contains notes as to how things are placed—all based upon my process as detailed above. Despite having addressed the ostensible futility of building comic book timelines, the Batman Chronology Project is definitely not a complete waste of time. This project is a labor of love and if you examine each panel of as many Batman stories as you can get your hands on, you will see that things do fit into a timeline in the most pleasantly unexpected ways. Of course, the frustratingly opposite happens almost just as often. But that is simply a part of the process. Theoretically, if the perfect suggested order is compiled, then we have the closest thing to answering our dreaded chronological question. Finding continuity is a game. It’s piecing together an impossibly intricate jigsaw puzzle. There’s no greater satisfaction than stepping back and seeing the final picture as a whole.

Regarding their occupation, the zoologist/psychologist couple David Barash and Judith Lipton say, “Although we seek ultimately to unravel genuine external truths about the natural world, not simply to validate our own preconceptions, one of those truths is that we are readily seduced by our own ideas and just as reluctant to give up on them—even in the face of contrary evidence—as anyone else.” I may not be trying to solve anthropological or biological mysteries by building superhero timelines, but this quote readily applies to my process. This site is meant to be entirely non-opinionated and nonobjective, and not some random fanboy list of my own personal favorite Batman stories. I’ll be the first to admit that I geek out a bit harder (and usually write a bit more positively) about my faves, and likewise, write a bit more negatively about things I don’t like as much. That being said, this does not mean that I’m trying to alienate any fans or tell any of my readers what’s good and what’s bad. I’ll leave that to the reviewers and the critics. This website is not a comic book review or critique site. This website is home to an intensive scholarly research project, through-in and throughout. There are a ton of stories I’ve included on my timelines that I despise and many more that I absolutely adore, which are absent since they are non-canon. I can’t stress this enough: the Batman Chronology Project is meant to be uninfluenced, unbiased, and, most substantively, a scientific research-based endeavor that examines the continuity of Batman via a narratological reading based solely upon the facts (admittedly as I see them) in the comic books themselves. Every tale—and I mean every tale—that is slotted into my chronology is done so only after a thorough examination of both narrative content and continuous in-story information. “Proof” comes from what’s literally found in the published materials combined with the application of Occam’s razor theory—the simplest explanation is likely the best. In the final calculus, however, there is no definitive right or definitive wrong when it comes to creating comic-book-world timelines. As the curmudgeonly genius Robert Anton Wilson quips, “I don’t think most issues in the sensory-sensual spacetime world (the world of experience) actually reduce to two-valued logic.” The same view can and should also be applied to Batman comics that exist in the sensory-sensual spacetime world of the DC multiverse and the greater omniverse (aka multi-multiverse) in which it dwells.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

Please click on the following link to continue reading the next part of this section: Who I am, How I Came to be.

_______________________________

_______________________________________________________________________________________

_______________________________

_______________________________

- [1]COLLIN COLSHER: Alex Damon of Star Wars Explained has an amazing video that discusses a broad strokes continuity conflict where a sequence from a comic book (Star Wars: Kanan – The Last Padawn #1) was re-shown on TV (Star Wars: The Bad Batch) with with some big (albeit mostly cosmetic) differences. Not only does Damon explain the concept of broad strokes really well, but he nicely sums up headcanon, reader-response, and the very nature of the interpretational aspect of multi-authored serial narrative as well! Damon says: “We have to start doing mental gymnastics. […] When [the continuity alteration] happened in The Bad Batch, I pretty quickly just altered how everything went down in my head. […] I found that the more I view each story in Star Wars as mythology, the more helpful it becomes. These tales we’re reading or watching aren’t a perfect representation of a real history. They’re stories being passed down from a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. Details might get muddled. […] If you take a step back from these stories and get a larger perspective, the details become less important, and in broad strokes, it all still lines up. […] And while I do find [continuity alteration] strange and—yes—annoying, it just doesn’t matter. I wish every story element fit together perfectly all the time, but that’s just not going to happen. Making videos like “The Complete Canon Timeline” have helped me think a little more flexibly. […] I’m not trying to say you shouldn’t be frustrated or anything when this stuff happens, but I am saying that it’s probably not going to stop happening, and this is how I deal with it as a Star Wars completionist myself. […] Should people consider The Bad Batch or the Kanan comic to be more correct? That’s a personal choice. Choose the version you like more because they both work together—y’know, if you squint a little bit. […] There’s absolutely nothing wrong with trying to enjoy [Star Wars] as a full-fledged history. I like to enjoy Star Wars that way. But if you’re going to do that, just recognize it’s not exactly a priority for the storytellers, and you’re probably going to have to be a little flexible in your thinking from time to time.”↩

- [2]COLLIN COLSHER: Unlike other chronology sites, like the amazing and inspirational Cosmic Teams by Michael Kooiman, the Batman Chronology Project doesn’t subscribe to a chronology-building methodology where comics that are clearly from a prior age can be canon in a later continuity. For instance, Silver Age comics from the 1960s cannot be canon in the Modern Age of the 1990s, or vice versa. However, I am aware that much Silver Age stuff has been referenced or flashed-back to in Modern Age comics, so in that sense, much of the Silver Age stuff has been preserved, albeit as a new Modern-ized version. Whenever there’s a reboot, the continuity or continuities of old are erased, but not in a literal sense. Instead, they form the skeletal framework (or urtext)—a freshly altered foundation for the new timeline. Other chronologies, including the aforementioned Cosmic Teams site, seem to do a type of chronology building where they keep the old stories intact as-they-were, and then add in caveats notating what must be ignored or what must have been altered to better suit the new continuity. I almost do the reverse, building my chronologies based off of what is being written, referenced, or flashed-back-to from current and ongoing comics within the new continuity, inserting versions of old stories as they are referenced or flashed-back-to by writers. The former methodology proves, with its caveats, that not everything from prior continuities can matter or count in a new rebooted continuity. Some things must be pre-reboot while others are decidedly post-reboot. You can’t have your cake and eat it too. Again, not to beat a dead horse, but building timelines and figuring out continuity consists of the literal act of interpreting story so that things make sense—and this includes reimagining stories to better fit contemporary narrative. Some single issue comics will contain material that reads as undeniably non-canon alongside stuff that reads as undeniably canon, sometimes even on the same page. This is precisely why you can never ever really say that a comic book from a previous era (i.e. previous continuity) is canon on the current timeline. A version of it can be canon, sure, but even if it’s almost 100% re-readable and can fit onto a new timeline unaltered, it’s still just some version of the original. It’s also important to understand that, even sans reference or flashback, anything from any older comic potentially may have happened. Don’t forget that building timelines is a purely subjective interpretive process.↩

- [3]MARTÍN LEL: A big misconception is whether comics from past continuities can be canon now. Some folks, for instance, say Jason Todd can never be counted as a Teen Titan member in later continuities because that happened in an earlier continuity only. On the other hand, people will say Frank Miller’s “Year One” is canon to the current Batman as is, despite being set in the 1980s. The truth lies in the middle—and although the why is complex, the how should be clear and succinct, something like “if a comic references a story from a past continuity, that past story is considered canon to the degree that the modern story has revealed, with the added caveat that it’s also adapted to fit with the current time period.” In short, the original story didn’t happen as it was published, but it did happen. I’d even go as far to add, “However, for the purposes of a reading order, you should read the old comic before the new one.” (Typically, the Batman Chronology Project is more oriented towards academic accuracy than a prospective reader’s journey.)↩

- [4]COLLIN COLSHER: Regarding my need for proof or evidence when it comes to canonization, I really don’t want to be the only authority on what is canon and what isn’t. I want the comic books themselves to function in that capacity. And by only regarding canon items that have been backed by ostensible proof gleaned from the page, I feel like I give space for the comics to speak their own truth. Some folks will strive for the canonization of as much material as possible, pushing for more and more while leaning on fanwanks and conjecture, but ultimately that isn’t my goal. I don’t want people to go to the Batman Chronology site to read “Collin’s timelines.” I want them to visit the Batman Chronology Project to read timelines that reflect interweaving published narratives as accurately as possible. Patrons can agree with what they read or they can use what they learn to better craft their own headcanon.↩

- [5]COLLIN COLSHER: Unlike at Marvel, where the “four years equaling one year” concept (the 4-1 rule) is always actively and openly in play, DC publishers and editors have never acknowledged use of any such formula, nor have any writers officially adhered to it. However, it’s clear that, following Zero Hour in 1994, the 4-1 rule was being applied to some characters—notably Tim Drake. While you may be able to make the 4-1 rule work with the DCU here-and-there, it doesn’t hold up well under scrutiny, especially if you are applying specific dates and times to the chronology. With the Marvel 4-1 rule, readers are basically directly told to ignore specificity of time and topicality. Maybe you don’t have to ignore these things on your first or second read through, but when you pick up that trade paperback five or ten years later, the details of the story will have somehow changed in order to fit the rule. In this sense, Marvel’s 4-1 rule dictates that narrative can never be set in stone, which means, with Marvel, one can’t really build a true timeline, only a reading order. Despite having said the above, there is a certain logic to the 4-1 rule, as it prevents having too wide a range of titles getting compressed into a single in-story year. After all, having ten years’ worth of publications kneaded into one in-story year isn’t ideal. And it’s even less ideal having said mega-packed year living next to a year that is half as compressed, right? Well, not exactly. These things only become problematic/not ideal depending on your end goal. If your end goal is to achieve some sort of well-balanced “perfect” symmetry, then yes, problems arise when you don’t utilize a strict law like the 4-1 rule. But if your end goal is less about arbitrary aesthetics, and instead revolves around finding sense and order via specific narrative (and my end goal is precisely this), then the 4-1 rule needn’t apply. I’m less invested in having the Silver/Bronze Age be preserved and well-balanced on the Modern Age timeline. (If it is, that’s great, but preservation and balance shouldn’t be the primary objective.) Instead, I view the Modern Age of DC as something truly new, in which the Crisis actually does erase the past, making it a skeletal framework that doesn’t have to look exactly like it used to. This erased past should bend and mold in order to better fit its new world—not the other way around.↩

- [6]COLLIN COLSHER: Some folks like to distinguish between an alternate timeline versus an alternate universe in the following way: by defining an alternate universe as a timeline that is wholly separate from the primary one; and by defining an alternate timeline as a timeline where everything is exactly the same as the primary timeline until a specific divergence point. And if one were to subscribe to the above definitions, then one might consider references or flashbacks from an alternate timeline as being canon on the primary timeline. However, talking about alternate timelines versus alternate universes is really just a matter of semantics. Ultimately, they mean the same thing—both are alternate realities. All throughout DC Comics (and almost every other superhero line), there are alternate timelines that are totally different from the primary timeline in every way imaginable. Likewise, there are alternate universes (i.e. specifically-labeled alternate Earths) that look like the primary timeline up until some divergence point, although there’s no actual way to determine where a true divergence point exists. Because of everything mentioned above, the Batman Chronology Project uses the terms alternate timeline, alternate universe, and alternate reality interchangeably—and it doesn’t consider references or flashbacks from alternate timeline material to be canonical.↩

Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson aren’t sharing a bed in those panels from Batman #117 you posted above. If you look at the headboards and the dividing line between their bedsheets, it’s clearly two separate beds next to each other.

I’m not saying that there aren’t Golden Age panels where Bruce & Dick ARE sleeping in the same bed out there, but this isn’t one of them.

Hi John! Thanks so much for the comment. This panel (from Batman #117) and a more famous one from Batman #84 have been tossed around the internet so much, they’ve become memes unto themselves. Sharing a bed or technically not sharing a bed, the effect is essentially the same—they are sharing a room with the beds pushed closely together. Make what you will of Bruce and Dick sharing a room/bed, but it’s mostly semantics in the end. Sadly, these curious panels undeniably (and quite unjustly) became primary “evidence” weaponized in Wertham’s insane anti-comics crusade.

(The panel from Batman #84 is probably a better example of Bruce and Dick “being in bed” with one another, but it doesn’t fit the example of an item requiring a retcon, so I didn’t use it for this particular section of my site. There are a ton of examples that I could have used that have nothing to do with the homoeroticism of Bruce/Dick, but I thought this was a fun one.)

Nevertheless, you make a very fine point, and the language I used is incorrect for sure. I’ll update now! Thanks, again.